-

How does it feel?

Willow bark is strongly bitter and astringent to taste. There is a slightly sour taste which follows due to the presence of its acidic compounds. A tincture of willow has a mildly anodyne and slightly aromatic sensation in the mouth. It can also be taken by chewing the bark. The leaves are less bitter and have a higher content of vitamin C.

-

What can I use it for?

As a febrifuge, willow is used to help manage fevers and treat viral infections such as flu (1). A herbalists’ treatment of virally induced fevers is different to that which is often recommended in the orthodox system of healthcare (which is to use pain relief and bring down the fever).

As a febrifuge, willow is used to help manage fevers and treat viral infections such as flu (1). A herbalists’ treatment of virally induced fevers is different to that which is often recommended in the orthodox system of healthcare (which is to use pain relief and bring down the fever).Fevers are the body’s natural way of fighting off a virus. The treatment of fevers is therefore more towards supporting the underlying immune functions that take place during a fever rather than to suppress them. The use of plant medicines to help manage fevers aims to encourage the immune function and detoxification through perspiration. This encourages the natural anti-pathogenic processes and allows the body to better eliminate the virus. Willow is second to none for this purpose as it also helps to reduce the uncomfortable body aches and pains associated with a fever. Please note that if fevers are over 39°C Celsius or higher, or if the fever has lasted for a few days then one should go to the hospital.

Willow can also be used to help manage the pain and inflammation of rheumatic conditions. It has mild analgesic properties which also make it an excellent choice for occasional headaches and other pain conditions. For headaches which recur for any longer than two weeks it is important to seek medical attention.

-

Into the heart of willow

Willow is both cool and dry energetically. These qualities make it most suitable for pain conditions that are associated with excessive heat and dampness. The most suitable applications will be where there is congestion and swelling such as that which is experienced in rheumatic conditions.

Willow is both cool and dry energetically. These qualities make it most suitable for pain conditions that are associated with excessive heat and dampness. The most suitable applications will be where there is congestion and swelling such as that which is experienced in rheumatic conditions.There will be hot, swollen, inflamed joints. It is also suitable for hot, throbbing headaches and helps cool and drain the vital force downwards.

Interestingly, willow is a plant that grows close to bodies of water such a streams and lakes. It thrives in these damp conditions. This correlates with its energetic properties to manage the balance of fluid and reduce congestion. Particularly that which is connected to joints.

Willowsbranches are also known as some of the most flexible of all trees. Which is why it is used in basketry and for a number of other structural and creative purposes. It is a plant which adapts and is pliable. Its qualities for more emotional applications may be applied in drop doses as a tincture to help with negative emotional states which need to be encouraged towards more flexibility.

In flower remedies willow is applied for inflexibility and resentment. Willow helps to bring about a sense of release for stuck feelings, allowing one to live in a state of optimism, faith and fluidity.

-

Traditional uses

White willow is the oldest recorded analgesic, or painkiller, in human history. White willow was also used in ancient Egyptian and Greek medicine as well. The famous Greek physicians Dioscorides, Hippocrates, and Galen recommended white willow to treat a fever and for the relief of pain.

It is also recorded that Chinese physicians have used white willow since 500 BC. It was traditionally used to relieve pain and reduce fevers. White willow was used in much the same way in Europe and some additional references were made for its applications as an antiemetic, to remove warts and suppress sexual desire.

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Western energetics

-

What practitioners say

Nervous system

Willow has long been used in the treatment of pain. The applications for inflammatory pain are mentioned below under the musculoskeletal system. Willow also works on pain receptors as an analgesic. It may be used in the treatment of headaches, lower backache and dental pain (1, 4, 5).

Musculoskeletal

A well-established use of willow is in the treatment of muscular and arthrodial rheumatism. It is also specific for other systemic connective tissue disorders such as gout and ankylosing spondylitis. It may be used to help manage inflammation and pain (1, 2, 3, 4).

Immune system

Willow may be used by a herbalist as part of an integrated approach to help reduce pain and inflammation in auto-immune conditions (3).

-

Research

There is a significant body of research into the efficacy of willow, particularly on rheumatic conditions and lower back pain. Willow has a long history of use in herbal medicine. It is well known that an important constituent called salicin from white willow is the compound from which the pharmaceutical painkiller aspirin is derived.

There is a significant body of research into the efficacy of willow, particularly on rheumatic conditions and lower back pain. Willow has a long history of use in herbal medicine. It is well known that an important constituent called salicin from white willow is the compound from which the pharmaceutical painkiller aspirin is derived.Salicin is metabolised to saligenin in the digestive system. It is after this metabolic and oxidisation process takes place that salicylic acid is formed in the liver and blood. The way that salicylic acid works is by inhibiting prostaglandins in the sensory nerves, thereby reducing pain (2).

Salicylic acid (SA) has well recognised anti-inflammatory and antipyretic properties which is how it is thought to be effective for arthritis. Acetylsalicylic acid (known as aspirin) is the synthetic form of SA which has additional anti-platelet properties due to the acetyl group. SA lacks this particular action which is why it is not an appropriate substitute for aspirin in cardiovascular disease (2).

Musculoskeletal

A systematic review was carried out to investigate the available studies on willow for the treatment of musculoskeletal pain. Seven manuscripts were reviewed each using ethanolic extracts of willow with daily doses up to 240 mg salicin over periods of up to six weeks. The review concludes that all studies indicate a dose-dependent analgesic effect which was described to be equal to rofecoxib (a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug) in patients with lower back pain (7).

A long-term study which saw four hundred and thirty-six patients with rheumatic pain caused by osteoarthritis (56.2%) and back pain (59.9%) was carried out using a willow bark extract Proaktiv® over a period of six months. The study allowed for co-medication with NSAIDS and opioids, which allowed the researchers to assess the safety in terms of herb-drug interactions. The study concludes that white willow bark can be used in the long-term therapy of painful musculoskeletal disorders. The study also confirms that it can be combined with NSAIDs and opioids if necessary, with no safety concerns (9).

Another double-blind randomised control trial was carried out to assess the effectiveness of white willow in the treatment of 78 patients with osteoarthritis. The primary outcomes measured pain, stiffness and physical function. The group were divided in half to either receive willow bark extract or placebo. The study shows that willow is an effective analgesic agent which can reduce pain in patients with osteoarthritis (10).

Cellular health

A study was conducted on an ethanolic extract of willow bark (called BNO 1455) on human colon and lung cancer cells. In the cells treated with the extract, cancerous cells were inhibited in many different ways. The cells’ ability to migrate (and therefore potentially metastasise) was reduced. The formation of tubules was also reduced, as was the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) which are both important factors for tumour growth. Furthermore, angiogenesis was reduced via the extract’s antioxidant mechanisms.

Angiogenesis is when new blood vessels are formed to oxygenate a tissue or in this case a tumour. The extract also promoted apoptosis which is programmed cell death. This is a favourable anticancer mechanism as it means that the cancer cells are destroyed without destroying healthy cells, the way for example chemotherapy does (6). It is important to note that whilst research conducted on cells can provide evidence for potential mechanisms of action, this may not actually translate into clinical use.

-

Did you know?

The compound from which aspirin was derived from was first isolated from the willow tree by Johann Buchner a German Pharmacologist (1783–1852). The active ingredient in willow bark was not discovered until 1828 when Johann Buchner first refined willow bark into yellow crystals and named it salicin (after Salix, the genus of the willow tree).

Additional information

-

Botanical description

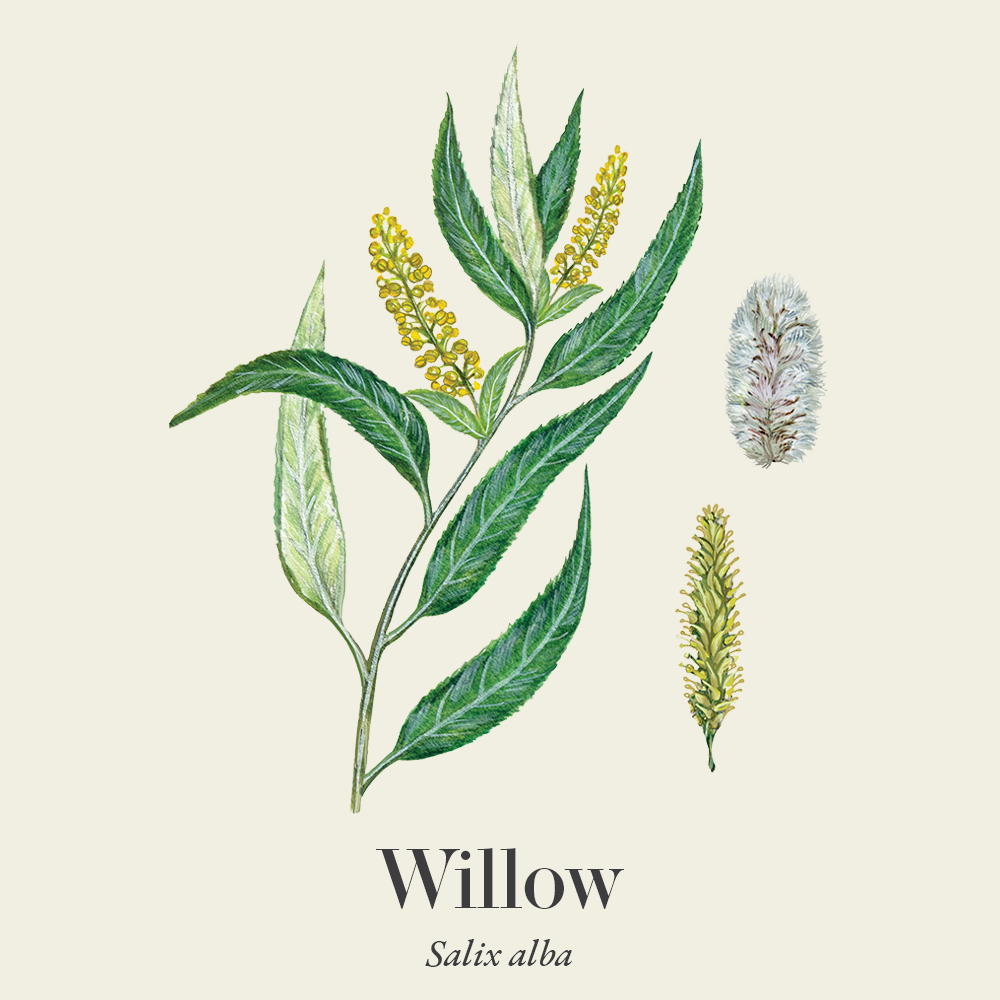

White willow is dioecious, meaning male and female flowers grow on separate trees. It is the largest species of willow. Mature trees can grow up to 25m high. They often have an irregular, leaning crown. The bark is light grey-brown and develops deep fissures with age, and twigs are slender, flexible and grey-brown.

The lanceolate oblong leaves can be up to 10 cm (3.9 in) long. The leaves are hairy all over at first then, as they age, remain downy underneath and sparsely hairy on the top. The leaf margin is finely serrated. Catkins appear in early spring – male catkins are 4–5 cm long and female catkins 3–4 cm long.

-

Common names

- White European willow

- Silver willow

- Basket willow

- Common willow

-

Safety

It is generally advised that willow should not be used during pregnancy and breastfeeding (5).

-

Interactions

Although willow is not thought to exert the same cardiovascular properties as aspirin, there is a possibility that it may slightly increase the effects of oral anticoagulants. It is best to avoid willow if you are taking anticoagulant medications (5).

-

Contraindications

Willow is generally not recommended for children because of the structural similarity of salicylic derivatives in willow bark to acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin). The use of aspirin is still associated with Reye’s syndrome, although with the availability of better diagnostic tools the number of reported cases appears to be declining (5).

Willow should be avoided by anyone with a history of aspirin allergy. The use of willow bark preparations should also be avoided in cases of sensitivity to salicylates.

-

Preparations

- Tincture

- Decoction

- Capsule

- Fresh bark

-

Dosage

Willow is generally not recommended for children. Seek advice from a qualified medical herbalist if your child needs support for a condition that willow bark can treat (5).

Tincture (1:5 25%): Take between 2-8ml three times a day.

Decoction: Place 1- 2 tsp of dried willow bark in 1 cup of water, bring to a boil and simmer for up to 25 minutes. This should then be strained, slightly cooled and drunk 3 times a day.

-

Plant parts used

The inner bark of willow is most often used in herbal medicine. It is usually harvested from the young branches of a mature tree. The young leaves may also be drunk as an infusion. However, it is thought to be less potent therapeutically.

-

Constituents

- Phenolic glycosides esters (up to 11%) Salicylin up to 10%

- Tannins unto 20%: as catechin, condensed tannin (procyanidin, allotannin)

- Flavonoids (up to 4%) (2)

-

Habitat

The white willow, is a species of willow native to Europe and western and central Asia. It typically grows near bodies of water on the banks of rivers and lakes or by ponds, streams, wet hollows and ditches.

-

Sustainability

According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants Status white willow has been assessed in Europe and is classed as ‘Least Concern as it is widespread with stable populations and does not face any major threats.’ (8).

According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants Status white willow has been assessed in Europe and is classed as ‘Least Concern as it is widespread with stable populations and does not face any major threats.’ (8).Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must therefore ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS). Read our article on sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Herbal Medicines are often extremely safe to take, however it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputed supplier. Sometimes herbs bought from unreputable sources are contaminated, adulterated or substituted with incorrect plant matter.

Some important markers for quality to look for would be to look for certified organic labelling, ensuring that the correct scientific/botanical name is used and that suppliers can provide information about the source of ingredients used in the product.

A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from. There is more space for contamination and adulteration when the supply chain is unknown.

-

How to grow

Willow is one of the easiest trees to grow. A young branch can be cut and planted straight into the earth. However, it is best to place willow cuttings into a bucket of water and wait for them to form roots first. They are fast-growing and interestingly they also contain a growth hormone which can be used to help cuttings of other plants take root (instructions below).

Willow is one of the easiest trees to grow. A young branch can be cut and planted straight into the earth. However, it is best to place willow cuttings into a bucket of water and wait for them to form roots first. They are fast-growing and interestingly they also contain a growth hormone which can be used to help cuttings of other plants take root (instructions below).- Once the roots become a couple of inches long, dig V-profile slots in the ground, about 10 inches deep and plant the willows in spacing them around 1-3 feet apart.

- The willow can grow successfully in full sun to slight shade. It prefers sandy to loamy to strong loamy soil and tolerates an acidic or alkaline ph.

- Willow requires regular watering. Especially in dry weather.

How to make willow rooting liquid

Steep the cut twigs in about 2 litres of boiling water, leaving them for about 24 to 48 hours. The willow can be strained off and the remaining tea-like fluid can be used to help cuttings of other plants take root.

-

References

- British Herbal Medicine Association. Scientific Committee (2003). A guide to traditional herbal medicines : a sourcebook of accepted traditional uses of medicinal plants within Europe. London: British Herbal Medicine Association.

- Menzies-Trull, C. (2013). Herbal medicine keys to physiomedicalism including pharmacopoeia. Newcastle: Faculty Of Physiomedical Herbal Medicine (Fphm).

- Bone, K. and Mills, S. (2013). Principles and practice of phytotherapy modern herbal medicine. 2nd ed. Edinburgh Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier.

- Hoffman, D. (2003). Medical Herbalism: The Science Principles and Practices Of Herbal Medicine. Hardback (1st Edition). Independently published

- Monographs, W. (2017). Salicis cortex. [online] Available at: https://escop.com/wp-content/uploads/edd/2017/09/Salix.pdf [Accessed 13 Jan. 2023].

- Hostanska, K., Jürgenliemk, G., Abel, G., Nahrstedt, A. and Saller, R. (2007). Willow bark extract (BNO1455) and its fractions suppress growth and induce apoptosis in human colon and lung cancer cells. Cancer Detection and Prevention, 31(2), pp.129–139. doi:10.1016/j.cdp.2007.03.001.

- Vlachojannis, J.E., Cameron, M. and Chrubasik, S. (2009). A systematic review on the effectiveness of willow bark for musculoskeletal pain. Phytotherapy Research, 23(7), pp.897– doi:10.1002/ptr.2747.

- Lansdown, R. (2013). IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Salix alba. [online] IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available at: https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/203465/42409554 [Accessed 16 Jan. 2023].

- Uehleke, B., Müller, J., Stange, R., Kelber, O. and Melzer, J. (2013). Willow bark extract STW 33-I in the long-term treatment of outpatients with rheumatic pain mainly osteoarthritis or back pain. Phytomedicine, 20(11), pp.980–984. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2013.03.023.

- Schmid, B., Lüdtke, R., Selbmann, H-K., Kötter, I., Tschirdewahn, B., Schaffner, W. and Heide, L. (2001). Efficacy and tolerability of a standardized willow bark extract in patients with osteoarthritis: randomized placebo-controlled, double blind clinical trial. Phytotherapy Research, 15(4), pp.344– doi:10.1002/ptr.981.

As a febrifuge, willow is used to help manage fevers and treat viral infections such as flu (1). A herbalists’ treatment of virally induced fevers is different to that which is often recommended in the orthodox system of healthcare (which is to use pain relief and bring down the fever).

As a febrifuge, willow is used to help manage fevers and treat viral infections such as flu (1). A herbalists’ treatment of virally induced fevers is different to that which is often recommended in the orthodox system of healthcare (which is to use pain relief and bring down the fever). Willow is both cool and dry energetically. These qualities make it most suitable for pain conditions that are associated with excessive heat and dampness. The most suitable applications will be where there is congestion and swelling such as that which is experienced in rheumatic conditions.

Willow is both cool and dry energetically. These qualities make it most suitable for pain conditions that are associated with excessive heat and dampness. The most suitable applications will be where there is congestion and swelling such as that which is experienced in rheumatic conditions. There is a significant body of research into the efficacy of willow, particularly on rheumatic conditions and lower back pain. Willow has a long history of use in herbal medicine. It is well known that an important constituent called salicin from white willow is the compound from which the pharmaceutical painkiller aspirin is derived.

There is a significant body of research into the efficacy of willow, particularly on rheumatic conditions and lower back pain. Willow has a long history of use in herbal medicine. It is well known that an important constituent called salicin from white willow is the compound from which the pharmaceutical painkiller aspirin is derived. According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants Status white willow has been assessed in Europe and is classed as ‘Least Concern as it is widespread with stable populations and does not face any major threats.’ (8).

According to the IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants Status white willow has been assessed in Europe and is classed as ‘Least Concern as it is widespread with stable populations and does not face any major threats.’ (8). Willow is one of the easiest trees to grow. A young branch can be cut and planted straight into the earth. However, it is best to place willow cuttings into a bucket of water and wait for them to form roots first. They are fast-growing and interestingly they also contain a growth hormone which can be used to help cuttings of other plants take root (instructions below).

Willow is one of the easiest trees to grow. A young branch can be cut and planted straight into the earth. However, it is best to place willow cuttings into a bucket of water and wait for them to form roots first. They are fast-growing and interestingly they also contain a growth hormone which can be used to help cuttings of other plants take root (instructions below).