-

How does it feel?

-

What can I use it for?

Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) Tea tree oil is only used topically often in a dilution or as part of a medicinal gel or cream. It is also often used in oral care products although it should not be ingested.

Tea tree is primarily known as an essential oil, which is widely used for its antimicrobial, antifungal, and anti-inflammatory properties. It is not typically used as a culinary herb and it is not recommended for internal use due to the potential for toxicity (1).The essential oil should not be underestimated for its strength and potency. It should always be used diluted, rather than neat on the skin. This is because the neat oil may be irritating and cause mild dermatitis and inflammation.

Tea tree can be used for many acute conditions of the skin including the treatment of stings, minor wounds, burns and skin infections of all kinds (1). The antiseptic and antifungal properties of tea tree have been widely researched. There is a significant evidence base for its efficacy in treating a wide range of bacterial and fungal infections (2).

It offers effective treatment of small boils, furuncles and some cases of mild bacterial acne. It has been shown to effectively treat tinea pedis (athletes foot) offering symptomatic relief of itching and irritation as well as directly targeting the fungal infection (1).

Tea tree is often included in oral care products due to its efficacy in the symptomatic treatment of minor inflammation caused by infections of the oral mucosa (1). It is effective against bad breath and gingivitis (3).

In addition to these well-known uses, tea tree oil is also a diaphoretic and expectorant. Tea tree oil can be incorporated into balms or creams or diluted into a carrier oil such as almond or jojoba to apply to the area of the chest for coughs and colds (2).

Diluted tea tree may also be used topically in the treatment of thrush and vaginal infections. Many herbalists make pessaries for this application; however, it should only be used acutely as the oils may negatively interfere with the PH balance of the vagina (2)

Tea tree is also often used for acne, athlete’s foot, verrucae, warts, insect bites, cold sores and as a deterrent for head-lice (2,3).

-

Into the heart of tea tree

Tea tree oil has an association of purification, cleansing and protection. It is a potent medicinal oil used in the defence against multiple bacterial and fungal pathogens. Its qualities are cooling due to its ability to reduce inflammation and infection, thus reducing pathological heat in the body (4).

-

Traditional uses

Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) Tea tree is native to Australia and its oldest known uses would lie with the indigenous tribes of Australia who have used tea tree as a medicine for thousands of years. The traditional application of this plant was through crushed leaves and poultices which were applied directly to the skin to treat wounds, infections, and skin conditions. A steam inhalation was used to alleviate colds and respiratory infections due to the potency of the essential oils (5,6).

Tea tree first came to the awareness of Western cultures after Captain James Cook’s expedition in 1770. It is believed that he and his crew brewed tea from the leaves, hence the name they employed for it — tea tree. There are, however, no reliable records of the traditional internal use of tea tree.

The medicinal use of the essential oil itself wasn’t documented in Europe until the early 20th century, when Arthur Penfold, an Australian chemist, published a series of scientific studies in the 1920s shedding light on its antimicrobial properties for the first time. It was these early studies that led to the popularity of tea tree oil as a potent antiseptic that is now used all around the globe (6,7).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

-

What practitioners say

Tea tree (Melaleuca alternifolia) Dentistry

Tea tree is used in many over-the-counter oral hygiene products due to a wide range of properties that can benefit the health of the gums. A mouthwash which includes tea tree oil may be useful in the treatment of gingivitis due to its antimicrobial properties that inhibit the growth of bacteria in the oral cavity. Its anti-inflammatory effects also help reduce gum swelling and bleeding gums (8).

Tea tree oil mouthwashes are also useful for managing halitosis (bad breath) due to the antimicrobial effects of its volatile oils which targets volatile sulphur compounds produced by oral bacteria that contribute to bad breath (3).

Immune system: Infectious diseases

Tea tree is perhaps most well known for its ability to help manage infections of bacterial and fungal nature. It is understood to disrupt the cell membrane of bacteria, leading to cell lysis and death (9). It is effective against antibiotic-resistant strains, like MRSA, by targeting multiple pathways (6).

Multiple studies have been carried out to explore the antifungal properties of tea tree oil. It works by inhibiting the growth of fungi by disrupting their cell membranes and interfering with their metabolic processes. It therefore addresses and targets fungal infections effectively and also reduces itching, redness, and scaling associated with infections like onychomycosis, candidiasis, tinea pedis (6,10,11). A mouthwash with tea tree is also useful for oral candida infection (12).

Tea tree may have some use in antiviral protocols, particularly for the treatment of skin based viral conditions such as herpes simplex (6). Studies have explored the effects of tea tree in conjunction with topical iodine in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum with positive results (13).

Dermatology

Tea tree’s anti-inflammatory and antibacterial properties make it useful in the management of many skin conditions. It has a long standing history of use for helping to address acne (14). It reduces the inflammation associated with acne and skin inflammations while its antimicrobial volatile oils target the specific bacteria (Propionibacterium acnes) associated with acne formation (3).

The antifungal activities of tea tree help in the treatment of dandruff. Tea tree is often incorporated into medicated hair products that target fungal dandruff causing scalp flaking, itching, and irritation (2,11).

Tea tree also promotes wound healing by reducing inflammation and preventing infection, thus facilitating tissue repair with a number of clinical studies demonstrating its ability to accelerate the healing process of minor wounds and cuts (3). Analgesic and antipruritic properties of tea tree oil are also often referenced (15).

-

Research

Tea tree oil (Melaleuca alternifolia) Tea tree oil has been extensively researched for over a century. A number of these studies have been included below to demonstrate the mechanism of action for some of the therapeutic actions of tea tree oil discussed in this monograph.

Two systematic reviews have been carried out that discuss and verify the efficacy of tea tree oil in many fields of medicine including dentistry, dermatology, infectious disease, ophthalmology, and podiatry. These reviews analyse the date from a wide range of human trials testing the therapeutic efficacy and safety of tea tree oil (3,15). Some of the most prominent studies are discussed below.

Please note: Animal studies are not condoned by Herbal Reality, however for the purpose of including research from which some understanding of therapeutic actions can be confirmed, some animal studies may be referenced within the works included herein.

The efficacy of 5% topical tea tree oil gel in mild to moderate acne vulgaris: A double-blind randomised trial

A randomised double-blind clinical trial was carried out to explore the effects of tea tree oil in a 5% topical gel on mild to moderate acne vulgaris. Sixty patients with mild to moderate acne were randomly divided into two groups and treated with tea tree oil gel or a placebo gel for a period of 45 days. The study results showed significant differences between the tea tree oil group in comparison with the placebo, with a greater improvement in the tea tree group. These results suggest that tea tree oil gel is an effective treatment for mild to moderate acne vulgaris(14).

Tea tree oil versus chlorhexidine mouthwash in treatment of gingivitis: A pilot randomised, double blinded clinical trial

Tea tree mouthwashes have been shown to be an effective treatment of gingivitis. A systematic review of studies using tea tree oil mouthwashes was carried out and demonstrated consistently positive outcomes including reduced gum inflammation, bleeding, and overall gum health (8).

These works afford us a deeper insight into the medicinal activities of this fascinating plant and show it has significant potential beyond many of its traditional uses.

-

Did you know?

The Aboriginal tribes of Australia used the leaves of the tea tree long before its discovery by Western explorers. The leaves would be crushed and made into a steam for inhalation to treat respiratory ailments. The oily poultice would have been used for wounds and infections. Tea tree was also used during World War II by Australian soldiers who are said to have applied it as a topical antiseptic for battle wounds (6).

Additional information

-

Botanical description

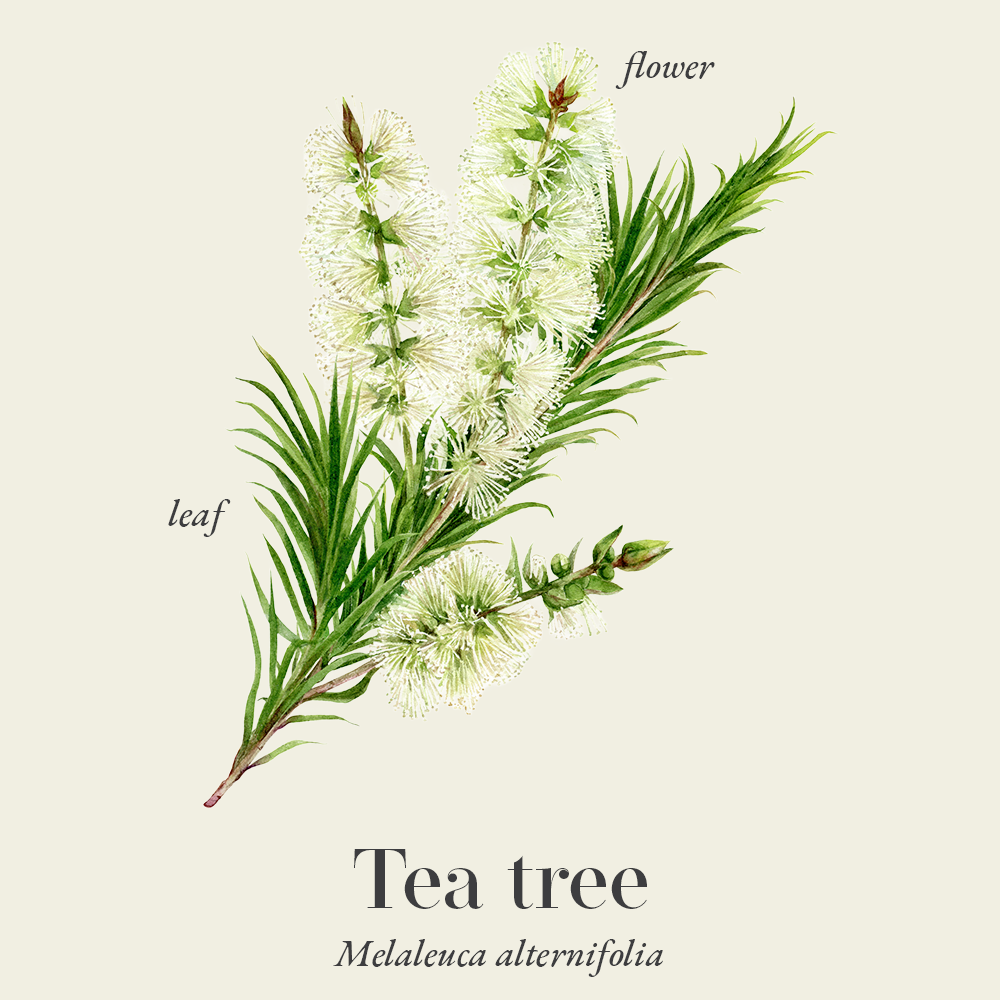

Tea tree is a small evergreen tree that can also grow like a shrub. It may grow up to around 7 metres tall. It has a bushy crown and whitish, papery bark. Its leaves are small, smooth and linear in shape (visually similar in some way to pine needles although they are much softer). The leaves grow to between 10–35 mm long and 1 mm wide and they appear alternately, sometimes scattered or whorled along its minor branches.

The leaves of tea tree are rich in volatile oils and have a distinct aromatic quality. Flowers occur in white or cream coloured masses of spikes 3–5 cm long in spring to early summer. These flowers viewed from a distance give the tree a feathery or fluffy appearance. In Autumn it produces small, woody, cup-shaped fruits which are around 2–3 mm in diameter, and are scattered along its branches (7). Tea tree is hermaphrodite. This means that it has both male and female organs. It is pollinated by insects (2).

-

Common names

- Narrow-leaved paperbark (referring to its thin, papery bark)

- Snow-in-summer (in reference to its white flowers that bloom profusely in summer)

-

Safety

Tea tree oil should be avoided during pregnancy and lactation.

Tea tree oil should not be taken internally. When ingested it may cause central nervous system depression and muscle weakness as well as sickness, nausea and many other side effects. In children, ingestion of tea tree oil is considered to be a medical emergency requiring immediate hospital treatment.

The use of tea tree oil in children under 12 years of age is not recommended.

Tea tree preparations that are designed for oro-mucosal use are deemed to be safe providing they are not ingested.

Using neat tea tree oil is not recommended as it may cause adverse skin reactions. These reactions are considered to be uncommon, however some may even have an allergic reaction. Side effects of use may include mild pruritus, burning sensation, irritation, erythema and swelling (contact dermatitis) (1,16,17).

-

Interactions

None known (1,16,17)

-

Contraindications

None known (1,16,17)

-

Preparations

- Essential oil

- Essential oil dilutions with gel

- Cream

- Balm

- Steam inhalations

-

Dosage

- Acne, boils, minor wounds, athletes foot, skin infections and insect bites: Topical preparation of 10% essential oil can be applied on the affected area 1–3 times daily. In some people an undiluted essential oil can be applied to the affected area 2–3 times daily although using the oil neat is not recommended.

- For the treatment of mucosal-oral conditions such as gingivitis and gum infections, a mouthwash can be used. Many over the counter mouthwashes are available. A dilution of 0.17–0.33 ml tea tree essential oil can be mixed in 100 ml of water to use as a rinse or gargle several times daily (1).

-

Plant parts used

Leaf

-

Constituents

- Volatile oils

- Monoterpenes: α-terpinene and p-cymene (antimicrobial and antioxidant); terpinen-4-ol (40–50% of the oil, antimicrobial); γ-terpinene (10–20%, antimicrobial); 1,8-cineole (eucalyptol, 5—10%, anti-inflammatory)

- Sesquiterpenes: Caryophyllene (anti-inflammatory and analgesic); bisabolene (calming effects and antimicrobial) (18)

-

Habitat

Tea tree is native to Australia. It grows mainly in southeast Queensland and the north coast as well as along the adjacent ranges of New South Wales. Its native habitats are usually along streams, on swampy flats (7).

-

Sustainability

Tea tree is not currently considered to be endangered or at risk in its native regions (19). Its habitats are considered to be affected by global warming and land use, however, these factors are not currently considered to be a threat to its stable populations (20).

Tea tree is not currently considered to be endangered or at risk in its native regions (19). Its habitats are considered to be affected by global warming and land use, however, these factors are not currently considered to be a threat to its stable populations (20).Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality and safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Good quality pure essential tea tree oil is said to be non-irritant. High quality oils contain about 40% terpinen-4-ol and 5% cineol. Whilst the latter is an irritant, these are reportedly well tolerated in this range for topical use. However, in poor quality oils the levels of cineol can exceed 10% and in some cases reach up to 65% (2).

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

How to grow

Tea trees require a lot of care and attention when growing outside of their natural habitat. They prefer full sun, so choose a location that gets at least 6–8 hours of direct sunlight. It will grow in well-drained, preferably sandy or loamy soil with a slightly acidic to neutral pH (around 5.5 to 7.5). Tea trees are unlikely to thrive outdoors unless they are planted in a USDA plant hardiness zone 8 or above (21). It is hardy to UK zone 9 (2).

- If growing from seeds, it’s best to start them indoors. Due to the time it takes to establish a young sapling, many choose to purchase a young tea tree or seedling from a garden centre.

- Start seeds in a seed mix, gently pressing them into the soil without covering them as they need some light to germinate. This should be done indoors 6–8 weeks before the last expected frost.

- Place the seedlings in a sunny window and make sure to keep soil moist with a little water every day. Germination should occur in 2–4 weeks.

- After the last threat of frost has passed and the seedlings have established their first set of leaves they can be transplanted outdoors when the soil has warmed up. Keep watering the young plants especially in the first few years.

- The trees require full sun to thrive, whether they are planted indoors or out. They will not be successful in the shade. Tea tree is drought tolerant once established and mature. They are not tolerant to consistent water logging of the soil. Yearly pruning in autumn will help maintain the plant’s shape and health (21).

-

Recipe

Tea tree oil (Melaleuca alternifolia) Tea tree oil gel

Ingredients

- 10 ml tea tree oil (100% pure, organic essential oil is best).

- 90 ml aloe vera gel (unscented and pure).

Method

- Using a small sterile glass bowl and spoon or spatula, blend the tea tree oil with the aloe vera gel. Make sure the ingredients are well combined.

- Decant the gel into a clean/ sterile dark glass container or a small pump bottle or jar.

- Store the gel in the refrigerator to increase shelf life and to further cool the product for a refreshing application.

-

References

- EMA. Melaleucae aetheroleum – European Medicines Agency. European Medicines Agency. Published November 22, 2021. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/herbal/melaleucae-aetheroleum

- Melaleuca alternifolia Tea Tree PFAF Plant Database. pfaf.org. Accessed on: November 22, 2024. https://pfaf.org/USER/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Melaleuca+alternifolia

- Abu El-Maaty MA, Raafat K, Al-Bakri AG, et al. The Efficacy of Tea Tree Oil in Health: A Review of Its Biological Activities and Potential Applications. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1116077. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1116077.

- Renovables. Tea tree oil: Properties, uses and warnings. Accessed October 11, 2024. Available from: https://renovables.blog/en/botany/tea-tree-oil-properties-uses-and-warnings/.

- The University of Arizona. Search Tree Collections. apps.cals.arizona.edu. Accessed on 04.10.24 https://apps.cals.arizona.edu/arboretum/taxon.aspx?id=824

- Carson CF, Hammer KA, Riley TV. Melaleuca alternifolia (Tea Tree) Oil: a Review of Antimicrobial and Other Medicinal Properties. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2006;19(1):50-62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1128/cmr.19.1.50-62.2006

- Wikipedia Contributors. Melaleuca alternifolia. Wikipedia. Published October 15, 2023. Accessed September 4, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Melaleuca_alternifolia#:~:text=5%20References-

- Ripari F, Cera A, Freda M, Zumbo G, Zara F, Vozza I. Tea Tree Oil versus Chlorhexidine Mouthwash in Treatment of Gingivitis: A Pilot Randomized, Double Blinded Clinical Trial. European Journal of Dentistry. 2020;14(1):55-62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1703999

- Cox SD, Mann CM, Markham JL. Interactions between components of the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia. J Appl Microbiol. 2001 Jul;91(3):492-497. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2001.01406.x.

- Satchell AC, Saurajen A, Bell C, Barnetson RS. Treatment of interdigital tinea pedis with 10% tea tree oil cream: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Australas J Dermatol. 2002;43(3):175-178. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0960.2002.00696.x.

- Satchell AC, Saurajen A, Bell C, Barnetson RS. Treatment of dandruff with 5% tea tree oil shampoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(6):852-855. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.122734.

- Huang L, Wu Z, Wu J, et al. Antimicrobial Activity of Tea Tree Oil and Its Component Terpinen-4-ol: A Review. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1116077. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1116077. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1116077/full.

- Piraccini BM, Alessandrini A, Dika E, Patrizi A, Tosti A. Treatment of molluscum contagiosum with a combination of iodine and tea tree oil: A prospective open study in 16 patients. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(3):349-352.

- Enshaieh S, Jooya A, Siadat AH, Iraji F. The efficacy of 5% topical tea tree oil gel in mild to moderate acne vulgaris: A double-blind randomized trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73(1):22-25. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.30646.

- Deng W, Zhong W, Hou X, et al. The Efficacy and Safety of Trilaciclib in Preventing Chemotherapy-Induced Myelosuppression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1116077. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1116077.

- Natural Medicines. Tea Tree Oil. naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Published 2024. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food

- Hoffmann D. Medical Herbalism – the Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Healing Arts Press; 2003.

- Borotová P, Galovičová L, Vukovic NL, Vukic M, Tvrdá E, Kačániová M. Chemical and Biological Characterization of Melaleuca alternifolia Essential Oil. Plants. 2022;11(4):558. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11040558

- Communications c=AU; o=The S of Q ou=Department of E and S ou=Corporate. Species profile | Environment, land and water. apps.des.qld.gov.au. Published October 20, 2014. https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/species-search/details/?id=14392

- Tran DB, Dargusch P, Moss P, Hoang TV. An assessment of potential responses of Melaleuca genus to global climate change. Mitigation and Adaptation Strategies for Global Change. 2012;18(6):851-867. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11027-012-9394-2

- StackPath. www.gardeningknowhow.com. Accessed September 4, 2024 https://www.gardeningknowhow.com/ornamental/trees/melaleuca-tea-tree/melaleuca-tea-tree-care.htm