-

How does it feel?

Nettle leaf, when cooked, has a taste and aroma similar to cooked spinach. The lack of strong taste and other impacts is also associated in traditional medicine with a diuretic action and this is one of the other distinguishing features of this plant.

The seeds have a deep, rich and mineral dense aroma, which comes through when tasted as a nutty and earthy flavour.

The root has a mild, earthy and grassy quality, with a mild flavour that comes through in the tea. The taste is slightly woody with undertones of hay and grass.

-

What can I use it for?

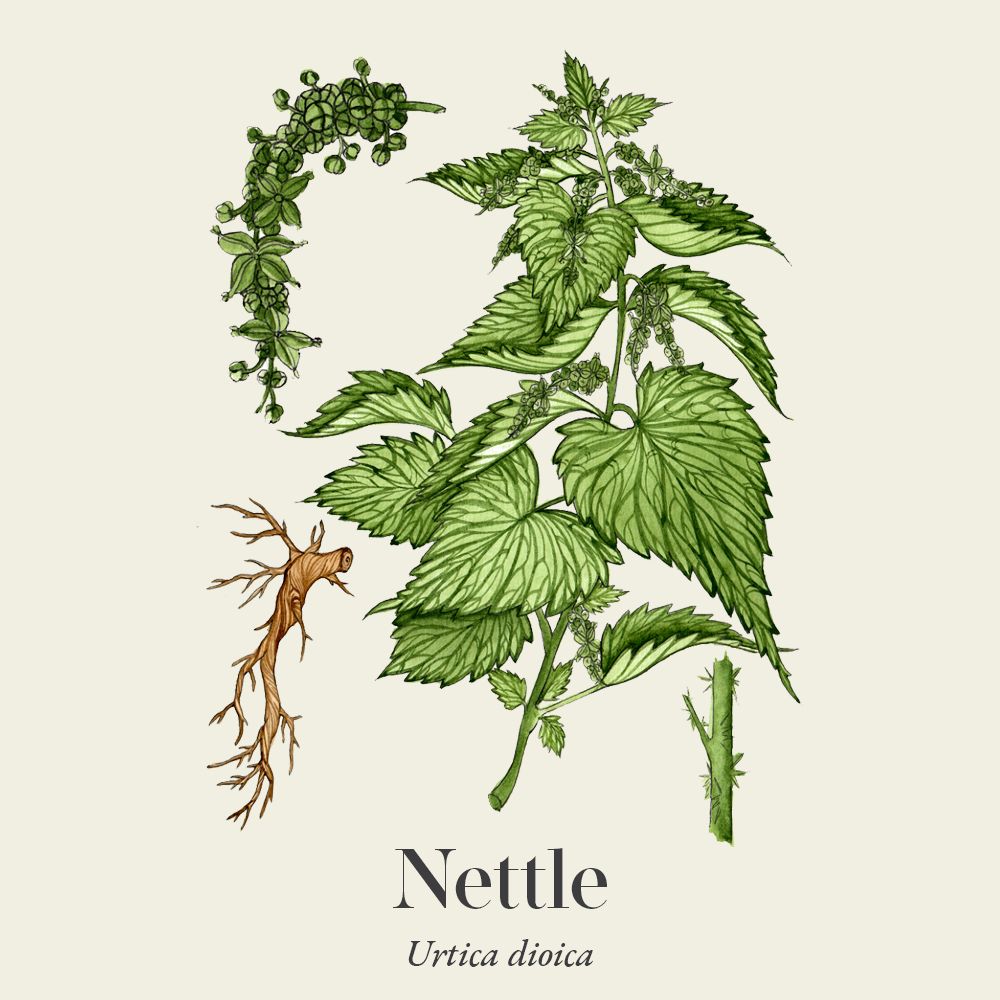

Nettle (Urtica dioica) Nettle leaf is incredibly nutritious — rich in iron, magnesium, calcium, chromium, zinc, potassium, phosphorus, and silicon; as such, nettle has been used as a valuable food source for thousands of years. The nutritional content, particularly the iron, makes this herb an excellent support for fatigue, convalescence after illness, and anaemia. The leaf can be harvested and added to soups and stews, or used fresh or dry as an infusion and drunk throughout the day (1,2).

Nettle is classed as a diuretic and helps to eliminate metabolites through the kidneys and urine. The best time to harvest the leaves is in spring, when they are young and tender, before the plant has flowered. Nettle leaf has a reputation as a spring tonic, as it helps to detox the body and nourish the body (1,2).

Traditionally, nettles have been used in Europe for relieving rheumatic conditions and associated joint aches and pains. Nettle leaves have been used to beat inflamed or arthritic joints, which promotes the release of histamine and formic acid to the area, triggering a counter-irritant effect. This effect essentially generates a healing response, and can reduce local inflammation by inhibiting inflammatory markers (3,4).

Nettles have antihistamine properties via multiple mechanisms of action, which indicate their use in treating allergic reactions and allergies such as hayfever (2,3).

Nettle root is most commonly known to treat benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) through a hormonal and anti-inflammatory action. It also helps to alleviate associated symptoms of the urinary system (2).

Nettle seeds are known as a kidney and adrenal tonic, and help to support the urinary system as well as build resilience to stress and illness (1,2).

-

Into the heart of nettle

Nettle tea (Urtica dioica) Nettle is sometimes described as a ‘pirate plant’ — it invades almost any environment and is often prolific enough to be classed as a troublesome weed. This is evidence of its ability to extract nutrients out of even the most challenging soil, and explains its rich nutritional properties.

It’s an incredibly nutritive herb that supports convalescence, nutritional deficiencies and anaemia as it helps to nourish and strengthen the body. It is sometimes referred to as a blood-builder as it aids in the formation of red blood cells (1).

Nettle leaves also have depurative/alterative actions alongside their nutritive quality, facilitating the excretion of toxic substances whilst rebuilding the nutritional stores. This alterative action coupled with its immunomodulatory action indicates nettle in the treatment of eczema, psoriasis, acne or other chronic skin conditions (1,2).

The flavonoids in nettle leaf are responsible for the antihistamine action, by inhibiting mast cell degranulation and suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines (5). Nettle helps to restore a sense of balance, particularly for allergic conditions affecting the skin or respiratory systems (2,6).

The astringent action of nettle leaf can be used to staunch bleeding both externally (as a tea) on a wound, or internally to help reduce heavy menstrual bleeding (1,7).

-

Traditional uses

Traditional indications for nettle leaf in Western herbal medicine include uterine haemorrhage, epistaxis and cutaneous eruptions. Medicinal monographs in Europe support the traditional use of nettle leaf in rheumatic and arthritic conditions. During Roman times, they often used nettle as a topical counter-irritant for the treatment of arthritic pain (7).

Nettle was traditionally known as a blood purifier and stimulating tonic. The Eclectics used the leaf to treat diarrhoea, dysentery and chronic diseases. The seeds were used in cases of consumption and goitre (8).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

Western actions

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Western energetics

-

What practitioners say

Skin health

Skin healthNettle is indicated in allergic skin conditions and reactions such as eczema, psoriasis, acne and allergic dermatitis, partly due to its ability to calm the allergic immune response but also because it helps purify the blood via promoting elimination through the liver and kidneys (1,8). Nettle can be used in an ointment or as a fresh juice to calm irritated skin conditions such as eczema, burns, bites and to accelerate wound healing (1,3).

Immune system

Nettle can effectively reduce inflammation by inhibiting pro-inflammatory cytokines including interleukin-1 (IL-1) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) and prostaglandin E2. This helps to modulate the immune system and reduce chronic inflammation associated with chronic conditions including allergies, chronic skin conditions and autoimmune diseases (7).

Nettle can reduce the allergic response by binding to H1 histamine receptors which block or modulate their activity. It also inhibits COX-1 and COX-2 inhibiting prostaglandin release and reducing inflammation. These actions make nettle useful in the treatment of allergic rhinitis (9).

Musculoskeletal system

Indicated where there is excessive acidity within the joints, such as in gout. Nettle will also act as a general diuretic, removing any excessive levels of heat and fluid around the joints, helping to relieve fluid retention and oedema (1,3).

Nettle is often used to treat rheumatic conditions, as it can suppress cytokine production and inhibit NF-kappaB, which is often elevated in chronic inflammatory diseases. Nettles have been shown to also reduce pain associated with musculoskeletal aches and pains. It also enhances the excretion of uric acid and, therefore, can be prescribed to treat rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and gout (1,10).

Endocrine system

Nettle can be used to regulate blood glucose levels, as it mimics the effects of insulin by increasing insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells (11). Nettle has been shown to positively impact hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes (11).

Digestive system

Nettle is a bitter herb and, therefore, stimulates the secretion of bile and increases lipid metabolism helping to balance cholesterol levels (12).

Urinary system

As nettle is a diuretic, it can help to reduce fluid accumulation and inflammatory congestion within the kidney and urinary systems. Nettle root can be used to reduce inflammation and treat benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), as the lignans and fatty acids inhibit binding of sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) to prostatic receptor sites. They also work by inhibiting aromatase, thereby preventing the conversion of testosterone into oestrogen, which reduces prostate enlargement (1,13).

Nettle seeds have traditionally been used as a kidney tonic, helping to support effective kidney and adrenal function. They can be included in a prescription to help increase resilience to stress and illness (1).

Reproductive system

The astringent action of nettle leaf can be applied to help reduce excessive menstrual bleeding, as well as support anaemic patients who are depleted from blood loss (1,2).

Nettle leaf is often used as a galactagogue to promote milk production in breastfeeding mothers (1,2).

-

Research

Nettle (Urtica dioica) Improved glycemic control in patients with advanced type 2 diabetes mellitus taking Urtica dioica leaf extract: A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial

This randomised, double-blind placebo controlled clinical trial evaluated the effects of nettle leaf on insulin levels in diabetic patients. One 500 mg capsule was given every eight hours for three months to 46 patients and compared to placebo. The results showed the extract significantly lowered fasting blood glucose levels, postprandial glucose and HbA1c when compared to placebo. This suggests nettle may be a safe and effective treatment to improve glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes (14).

Antihypertensive indigenous lebanese plants: Ethnopharmacology and a clinical trial

Nettle is a frequently prescribed herb for hypertension in Lebanon, in this clinical trial nettle extract was prescribed at a dose of 300 ml in patients with mild hypertension over a course of 16 weeks. The results showed significant reductions in systolic, diastolic, and mean arterial blood pressure when compared to placebo. This suggests nettle could be a safe and effective herb in the treatment of hypertension (15).

Phytalgic, a food supplement, vs placebo in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial

This randomised, double blind clinical trial tested Phytalgic (a food supplement containing fish oil, vitamin E and nettle) compared with placebo amongst 81 patients with osteoarthritis over three months. The aim was to explore whether using this supplement could reduce the necessity for using NSAIDs. Results showed that Phytalgic reduced the need for analgesics and improved symptoms of osteoarthritis when compared to placebo (16).

A review of the effects of Urtica dioica (nettle) in metabolic syndrome

This review explored the use of nettle as an antihypertensive, antihyperlipidaemic and antidiabetic by looking at multiple in vitro, animal and clinical studies. The results suggested that nettle was consistent in lowering both systolic and diastolic blood pressures through vasodilation, calcium channel blocking and diuresis. Animal and human studies confirmed that nettle was effective in reducing total cholesterol, LDL and triglycerides whilst improving HDL levels. This was found to occur via antioxidant effects preventing lipid peroxidation, HMG-CoA reductase inhibition and activation of PPAR enhancing fatty acid oxidation.

Finally, nettle was also found to improve glycaemic control in human and animal studies by increasing insulin secretion, regenerating pancreatic β-cells, inhibiting carbohydrate-digesting enzymes (α-amylase, α-glucosidase), reducing intestinal glucose absorption, and enhancing insulin sensitivity (11).

Urtica dioica in comparison with placebo and acupuncture: A new possibility for menopausal hot flashes: A randomised clinical trial

This double-blind, randomised controlled trial explored the effect of (a) Urtica dioica 450 mg/day and acupuncture 11 sessions, (b) acupuncture and placebo, (c) sham acupuncture and nettle and, (d) sham acupuncture and placebo, in 72 postmenopausal women experiencing hot flushes over a course of seven weeks with a four week follow up. Results showed that hot flushes were significantly reduced in groups a, b and c with no improvement in group d. These results show nettle could be considered as an effective form of treatment for hot flushes (17).

A comprehensive review on the stinging nettle effect and efficacy profiles. Part II: Urticae radix

A total of 246 participants took part in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicentre study to investigate the effects of nettle root extract on benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH). They were administered with 459 mg, and results showed a significant reduction in International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) when compared to placebo. Results show that nettle root has an anti-inflammatory effect and it is likely that epidermal growth factor, prostate steroid membrane receptors and sex hormone binding globulin are involved in the antiprostatic effect (13).

The efficacy of stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH): A randomised double-blind study in 100 patients

This study investigated the effects of nettle (Urtica dioica) on symptoms of BPH in 100 men aged between 40–80. They were divided into two groups with one being given 300 mg of nettle twice daily and the other placebo for eight weeks. Symptoms were assessed weekly using the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS/AUA). The nettle group was found to have a significant reduction (from 26.5 at baseline to 2.1) in symptoms compared to placebo (18).

-

Did you know?

‘Grasping the nettle’ is a familiar country trick. If you grasp a stinging nettle firmly from the base you can run your closed hand up the plant with few or even no stings — the stinging hairs point upwards.

The fibres from nettle have traditionally been used to make cloth. They have a similar feel as linen or cotton and were used during the first world war as a cotton substitute (19).

Additional information

-

Botanical description

Nettle is a perennial herb, growing to between 25–150 cm in height and covered all over with brittle stinging hairs. The leaves are a dark green and deeply serrated with pale pink flowers and seeds appearing on long drooping stems that protrude from the stem and leaf itself. It has shallow, branching yellow roots. Nettles grow wild in a variety of locations, but are most common in hedgerows, wood margins, waste ground, meadows, gardens and roadsides (3).

Urtica urens is a similar looking annual herb, with shorter, rounder (less heart-shaped) leaves that prefers drier terrain. This species has a similar phytochemical profile, and so can be used interchangeably with Urtica dioica.

-

Common names

- Stinging nettle (Eng)

- Haarnesselkraut (Ger)

- Brennesselwurzel (Ger)

- Haarnesselwurzel (Ger)

- Herbe d’ortie (Fr)

- Racine d’ortie (Fr)

- Ortica (Ital)

- Brændenælde (Dan)

-

Safety

Nettle leaf should be avoided during pregnancy due to its uterine stimulant actions. It should only be taken during breastfeeding under the supervision of a medical herbalist (20).

Handling the fresh herb can be irritant to the skin due to the miniature hairs injecting histamine and acetylcholine into the skin (2).

-

Interactions

Caution is advised alongside antidiabetic and antihypertensive medication, as well as diuretics (1,20).

-

Contraindications

People with a known allergy to nettle stings should not apply the fresh or processed dried leaves topically to the skin in any form (8).

It should be avoided in those with oedema resulting from cardiac or renal impairment (1).

-

Preparations

- Tincture

- Dried

- Powdered

-

Dosage

- Tincture (ratio 1:5 | 25%): 2–6 ml three times a day (leaf)

- Infusion/decoction: 6–30 g/day of dried leaf as a tea; 4–6 g/day of dried root by decoction or as a tea

- Fresh juice: 5–10 ml three times a day (2,3,8)

-

Plant parts used

- Leaf

- Root

- Seed

-

Constituents

Nettle leaf constituents

- Flavonoids: Quercetin, rutin, kaempferol and isorhamnetin

- Phenolic compounds: Vanillin, vannilic, ferulic, caffeoylmalic and chlorogenic acids

- Amines: Acetylcholine, histamine and serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine), predominantly in the small hairs.

- Sterols: P-sitosterol

- Triterpenoids: Ursolic acid

- Tannins

- Omega-3 fatty acids (3,8)

Nettle root constituents

- Lectins: Agglutinin

- Coumarins: Scopoletin

- Sterols: β-sitosterol

- Fatty acids

- Polysaccharides

- Oleoresin (3,8)

-

Habitat

Nettle is native to Europe and temperate parts of Asia; however, it can now be found growing globally worldwide. It prefers moist environments, including riverbanks, meadows, woodlands, gardens and roadsides. Nettle prefers nutrient rich, moist soils with high nitrogen content, often found in habitats previously disturbed by humans or animals (21,22).

-

Sustainability

Nettle is classified as ‘least concern’ on the IUCN redlist, as populations are considered stable with no major threats worldwide (23,24). Nettles are considered a robust plant that grow abundantly in the wild (23,24).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

How to grow

Nettle will thrive in nutrient rich soil, and will prefer full sun to partial shade. To propagate from seeds, sow the seeds in early spring and gently press them into rich compost without burying them too deep as they will need sunlight to germinate. Stratifying the seeds beforehand will increase the chances of germination. Germination should take between 10–14 days. Plant the young plants out when they have reached 4–6 inches tall.

Nettles can become invasive due to their spreading rhizomes so it is best to plant them in beds to maintain them in one area. Nettles will die back after the frost, but will regrow from the roots in the spring. The best time to harvest nettle for food or medicine is in the spring before the plants begin to flower (25).

-

Recipe

Nourishing nettle tea

Earthy, herbaceous, grassy and brimming with minerals, this nourishing nettle tea is a quintessential herbal brew.

Ingredients

- 30 g/1 oz nettle leaf

- This will serve 2–3 cups of nettle brew.

How to make nettle tea

- Put the nettle leaf in a pot.

- Add 500 ml (18fl oz) cold water.

- Leave to steep for 2–4 hours (or even overnight) and then strain for a truly nourishing brew that you can drink throughout the day.

-

References

- Mcintyre A. Complete Herbal Tutor : The Definitive Guide to the Principles and Practices of Herbal Medicine (Second Edition). Aeon Books Limited; 2019.

- Thomsen M. Phytotherapy Desk Reference. 6th ed. Aeon Books; 2022.

- Fisher C. Materia Medica of Western Herbs. Aeon Books; 2018.

- Dieppe P. Osteoarthritis of the knee in primary care. BMJ. 2007;336(7636):105-106. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39412.592477.80

- Park HH, Lee S, Son HY, et al. Flavonoids inhibit histamine release and expression of proinflammatory cytokines in mast cells. Archives of Pharmacal Research. 2008;31(10):1303-1311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12272-001-2110-5

- Rakha A, Umar N, Rabail R, et al. Anti-inflammatory and anti-allergic potential of dietary flavonoids: A review. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2022;156:113945. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113945

- Bhusal KK, Magar SK, Thapa R, et al. Nutritional and pharmacological importance of stinging nettle (Urtica dioica L.): A review. Heliyon. 2022;8(6):e09717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09717

- Bone K, Mills S. Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine. 2nd ed. Edinburgh Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier; 2013.

- Roschek B, Fink RC, McMichael M, Alberte RS. Nettle extract (Urtica dioica) affects key receptors and enzymes associated with allergic rhinitis. Phytotherapy Research. 2009;23(7):920-926. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.2763

- Riehemann K, Behnke B, Schulze-Osthoff K. Plant extracts from stinging nettle (Urtica dioica ), an antirheumatic remedy, inhibit the proinflammatory transcription factor NF-κB. FEBS Letters. 1999;442(1):89-94. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0014-5793(98)01622-6

- Bahareh Samakar, Soghra Mehri, Hosseinzadeh H. A review of the effects of Urtica dioica (nettle) in metabolic syndrome. National Centre for Biotechnology information. 2022;25(5):543-553. https://doi.org/10.22038/ijbms.2022.58892.13079

- Domjanić Drozdek S, Odeh D, Đikić D, et al. The Effects of Nettle Extract Consumption on Liver PPARs, SIRT1, ACOX1 and Blood Lipid Levels in Male and Female C57Bl6 Mice. Nutrients. 2022;14(21):4469. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14214469

- Chrubasik JE, Roufogalis BD, Wagner H, Chrubasik S. A comprehensive review on the stinging nettle effect and efficacy profiles. Part II: Urticae radix. Phytomedicine. 2007;14(7-8):568-579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phymed.2007.03.014

- Kianbakht S, Khalighi-Sigaroodi F, Dabaghian F. Improved Glycemic Control in Patients with Advanced Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Taking Urtica dioica Leaf Extract: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Clinical Laboratory. 2013;59(09+10/2013). https://doi.org/10.7754/clin.lab.2012.121019

- Samaha AA, Fawaz M, Salami A, Baydoun S, Eid AH. Antihypertensive Indigenous Lebanese Plants: Ethnopharmacology and a Clinical Trial. Biomolecules. 2019;9(7):292. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom9070292

- Jacquet A, Girodet PO, Pariente A, Forest K, Mallet L, Moore N. Phytalgic®, a food supplement, vs placebo in patients with osteoarthritis of the knee or hip: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2009;11(6):R192. https://doi.org/10.1186/ar2891

- Kargozar R, Salari R, Jarahi L, et al. Urtica dioica in comparison with placebo and acupuncture: A new possibility for menopausal hot flashes: A randomized clinical trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2019;44:166-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2019.04.003

- Ghorbanibirgani A, Khalili A, Zamani L. The Efficacy of Stinging Nettle (Urtica Dioica) in Patients with Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: A Randomized Double-Blind Study in 100 Patients. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal. 2013;15(1). https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.2386

- Viotti C, Albrecht K, Amaducci S, et al. Nettle, a Long-Known Fiber Plant with New Perspectives. Materials. 2022;15(12):4288. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15124288

- Natural Medicines Database. Stinging nettle. Therapeuticresearch.com. Published 2025. Accessed August 22, 2025. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/Data/ProMonographs/Stinging-Nettle#safety

- Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. Urtica dioica L. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science. Plants of the World Online. Published 2025. Accessed June 16, 2022. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:260630-2

- The Wildlife Trusts. Stinging Nettle | the Wildlife Trusts. www.wildlifetrusts.org. Published 2024. https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/wildflowers/stinging-nettle

- Lansdown R. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Urtica dioica. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published June 18, 2014. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/167815/63741582

- The Royal College of Physicians . The Garden of Medicinal Plants. Rcplondon.ac.uk. Published 2025. Accessed August 22, 2025. https://garden.rcplondon.ac.uk/plant/Details/1677

- Buckner H. How to Grow Stinging Nettle. Gardener’s Path. Published April 21, 2020. https://gardenerspath.com/plants/herbs/grow-stinging-nettle/