-

How does it feel?

The immediate impression upon tasting motherwort tea is its bitterness. This taste is quickly followed by a modest, sharp, acrid quality. However, these tastes do not linger for long and leave a residual aromatic flavour in the mouth.

These qualities are a reminder that motherwort acts on bitter receptors and are suggestive of its impact on digestive and liver function.

-

What can I use it for?

Motherwort is associated with calming anxiety symptoms, especially when they manifest in the chest. It promotes a sense of calm and compliments breathing exercises that focus on reducing tension in the diaphragm.

Tension and anxiety are often associated with tightness in the diaphragm and ribcage — this amplifies heart sounds, causing a heightened awareness of the heart beating, and also interferes with digestive transit.

A routine of breathing exercises to expand the diaphragm is important to manage this symptom of anxiety, and motherwort is a supportive tool in this exercise.

In this regard, a cup of motherwort tea is effective in supporting anxiety where the symptoms manifest as heart palpitations, hyperventilation, hiatus hernia and swallowing difficulties (1,2)..

Motherwort (suggestive of its name) is a key herb in supporting women’s reproductive health, especially during periods of transition including menarche, childbirth and menopause. It helps to ease these transitions by supporting both the nervous and cardiovascular systems. It is a uterine tonic and helps to regulate the menstrual cycle, specifically in cases where stress or tension can cause irregular cycles and bleeding (2,3).

-

Into the heart of motherwort

Motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca) The common and botanical name of this plant are key indicators of its modern and traditional usage. Motherwort (‘mother plant’) suggests its traditional usage to support female health, particularly menstrual and uterine based conditions affecting fertility and conception. The Latin specific cardiaca (and the German common name Herzgespann) is indicative of the plant’s affinity for treating heart related disorders, particularly where the condition may be exacerbated by emotional stress.

In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), motherwort is considered a herb that helps to circulate the uterus qi. These qualities make motherwort a choice herb for regulating the menstrual cycle and addressing conditions in the female reproductive system. It is also used to circulate heart qi and to dispel wind heat (4).

Energetically, motherwort is considered cooling and dry with bitter, aromatic and acrid qualities (4). It is due to its acrid action that it works well in cases of constricted or atrophic tissue states. Acrid herbs are often used for constrictive tissue states because the bitter compounds responsible for the acrid qualities trigger reflexes in the autonomic nervous system (ANS) by the vagus nerve.This affects the epithelial tissues that line the visceral organs associated with ANS function (cardiovascular, reproductive, digestive, nervous and urinary ) (5).

Motherwort has a specific affinity for the heart. This refers to both the emotional and physical aspect of the heart. Motherwort is indicated in cases presenting with a picture of cardiac ‘feebleness’, where there may be symptoms of palpitations, high blood pressure and a weak yet rapid heart rate (5).

It also has an affinity for the spine and pain in the pelvic and lumbar regions. It can be used as a nerve tonic to include in cases of spinal irritation. Matthew Wood describes motherwort as specific in emotional cases of ‘excessive emotionality’. He describes that patient as red faced (but not with anger) with staring eyes or a nervous expression (5).

In more modern medicine, its uses extend to hyperthyroidism (for the cardiac symptoms), palpitations, nervous tachycardia, secondary amenorrhoea, dysmenorrhoea, ovarian pain, anxiety, neuralgia, and can be useful for menopausal hot flushes and a general menopausal aid (3,4).

-

Traditional uses

Motherwort is used to support menstrual irregularity and associated menstrual conditions in both Europe and China. The herb most often used in China is a botanically related species Leonurus heterophyllus; however, both species have similar medicinal and pharmacological uses.. Its reputation for improving mood has been a consistent theme since the Mediaeval era. The English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper considered motherwort useful for removing melancholy vapours from the heart, improving cheerfulness, and settling the wombs of mothers.

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

Western actions

Ayurvedic actions

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Chinese energetics

-

What practitioners say

Cardiovascular system

Cardiovascular systemMotherwort is useful in any heart condition exacerbated by stress. It is specifically indicated in palpitations, tachycardia and angina and when the heart is under high levels of emotional distress, for example during a period of grieving or heartbreak (6,8).

It may be used to help treat high blood pressure due to its tonic action on the cardiovascular system . As a cardiotonic, motherwort directly supports the heart muscles that produces a regulating and strengthening effect on heart function (6,8).

Endocrine system

In TCM, motherwort is commonly used in the treatment of hyperthyroidism as it is believed to have thyroid inhibiting effect (4). Its effects on the cardiovascular system are particularly important for managing associated symptoms of hyperthyroidism. It helps to reduce tachycardia and heart palpitations that often accompany this condition (6).

Reproductive system

Motherwort can be used in any condition affecting uterine function. It is classed as a uterine tonic, strengthening and nourishing the uterus in preparation for childbirth, as well as supporting and strengthening it postpartum. It is specifically indicated where menstruation is delayed or suppressed as a result of emotional tension (5).

Motherwort is also indicated for dysmenorrhea, amenorrhoea, fibroids and anxiety during menopause. It is not only a tonic for the reproductive tissues, but also relieves tension through its antispasmodic action (2,6).

Urinary system

Motherwort has an affinity for the urinary system and can be used to support kidney health. It is indicated in cases of kidney fluid congestion and water retention due to its diuretic effect. Thus it can help to address conditions such as oedema, albuminuria, nephritis and chronic prostatitis (2,6). Motherwort helps to detoxify the blood of excess proteins through increased elimination of waste products via the kidneys. It may also be useful where there is blood in the urine caused by kidney stones (5).

-

Research

Motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca) There is currently very little research into the medicinal actions of motherwort. Almost all of the supporting literature is from classic herbals. There are a small number of in vivo and in vitro studies included below that focus on compounds found in motherwort which demonstrate a variety of its effects.

A systematic review was carried out to investigate the effects the motherwort used in TCM (Leonurus japonicus), administered in the form of an injection (a preparation primarily composed of the herb’s constituents leonurine and stachydrine) to reduce bleeding after childbirth and caesarean section. Forty-six randomised controlled trials were analysed with many comparing the effects of motherwort with oxytocin and some combining the two. The results from both showed significantly lowered blood loss within two and 24 hours, and reduced risk of complications and adverse events. Motherwort injection combined with oxytocin also decreased the risk of postpartum haemorrhage (9).

Motherwort has been shown to exhibit antioxidant effects through in vitro research. Whilst, in vivo studies have established hypotensive and vasorelaxant effects of leonurine, a compound in motherwort. Uterotonic effects from some of its active constituents; lavandulifolicide and verbascoside have also been identified. Whilst a compound called stachydrine was identified as having oxytocic effects via in vivo research (10).

-

Did you know?

The botanical name, Leonurus, given to the plant by the leading plant taxonomist Linnaeus, reflected an early common association and name, lion’s tail.

Additional information

-

Botanical description

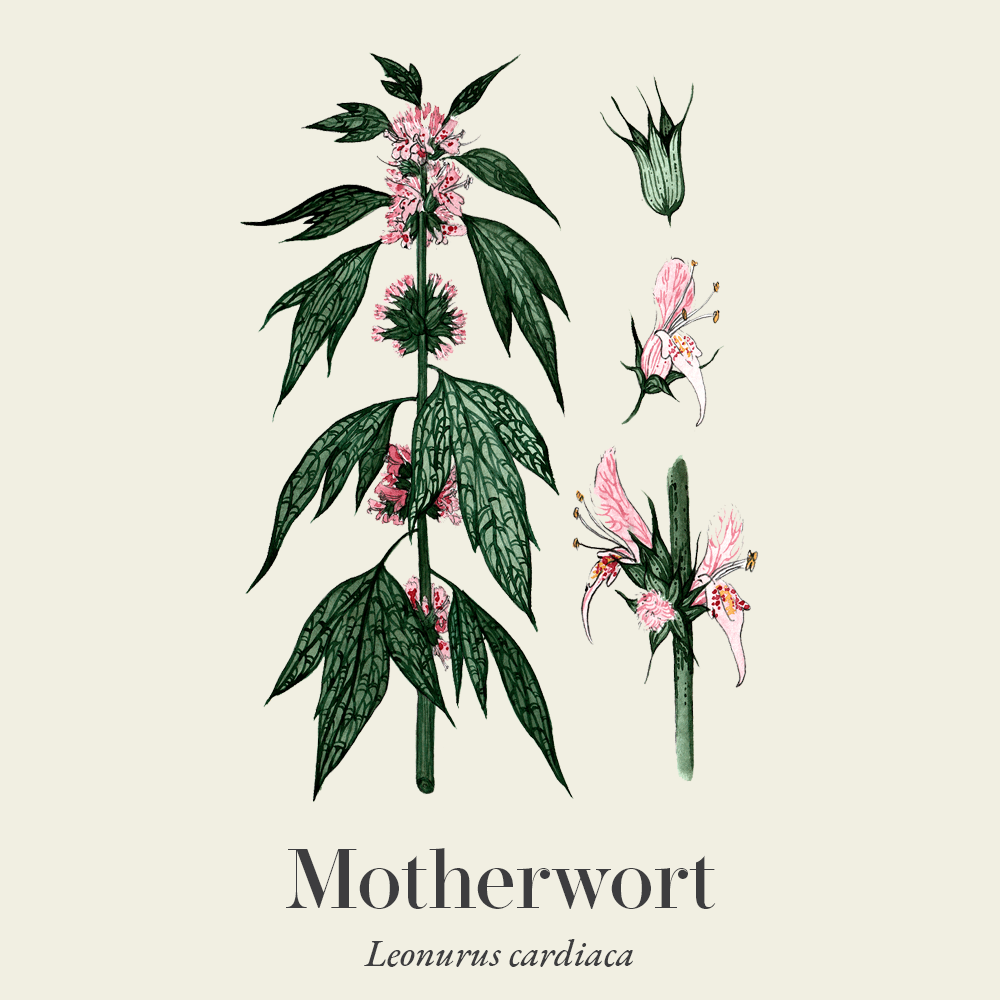

Motherwort is a herbaceous, perennial member of the mint family. It is native to Europe and will grow naturally in hedgerows, banks and most often in calcareous soils. Its most distinguishable feature is the leaves, which are palmately cut into separate lobes or three-pointed segments and have a layer of soft hairs covering the surface.

The plant can grow to 1–2 meters in height and produces whorls of pinky-white flowers that also display a thick layer of hairs. Like other Labiates it has a characteristic square (quadrilangular) stem (12).

-

Common names

- Lions tail

- Lions ear

- Throw wort

- Herzgespann (Ger)

- Agripaume (Fr)

- Agripalma (Sp)

- Cardiaca (Sp)

- Yi mu cao (Chin)

-

Safety

It is best avoided in early pregnancy, and only used during the final few weeks. However, it is best to consult with a medical herbalist for guidance on taking motherwort at any time during pregnancy (2,3).

It may increase menstrual flow (3).

-

Interactions

Theoretically it may increase the action of CNS depressants (11).

-

Contraindications

None known (2,3,6)

-

Preparations

- Tincture

- Infusion

- Plant part used

-

Dosage

- Tincture (ratio 1:5 | 25%): Take between 1–3 ml in a little water up to three times a day.

- Infusion/decoction: To make an infusion, place 2–4 grams of dried material into one cup of boiling water, and infuse for up to 10 minutes. This should be drunk hot three times a day (3).

-

Plant parts used

Aerial parts (flower and leaf)

-

Constituents

- Bitter iridoid glycosides: Leonuride, ajugol, galiridoside

- Terpenes

- Diterpenes: Labdanes including leocardin

- Triterpenes: Ursolic acid

- Alkaloids (trace): Leonurine and stachydrine.

- Flavonoids: Kaempferol, apigenin and quercetin

- Tannins (5–9%): Hydrolysable and condensed

- Other constituents: Phenolic acids (caffeic acid), phenylpropanoids (verbascoside, lavandulifolioside), terpenoids (caryophyllene and α-pinene)

-

Habitat

Motherwort is thought to be native to the southeastern part of Europe and central Asia and was introduced to the UK and North America Its natural habitat is beside roadsides, in vacant fields, waste ground, rubbish dumps and other disturbed areas (13).

-

Sustainability

At risk from overharvesting and habitat loss. Read more in our sustainability guide. Motherwort is classed as Least Concern on the IUCN database of threatened species. In many regions it is widespread with stable populations which means there is currently a low risk of extinction in Europe. However, due to unregulated collection from the wild for medicinal and cosmetic industries the population decline has been reported in several of its native countries. This species is also currently not widely cultivated for medicinal products or otherwise. It is therefore classed as ‘at risk’ on various national red lists (14,15).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must, therefore, ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that affect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Herbal medicines are often very safe to take; however, their safety and efficacy can be jeopardised by quality issues. So, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputable supplier, from sources known to test their herbs to ensure there is no contamination, adulteration or substitution with incorrect plant matter, as well as ensuring that recognised marker compounds are at appropriate levels in the herbs.

Some important quality assurances to look for are certified organic labelling, the correct scientific/botanical name, and the availability of information from the supplier about ingredient origins. A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from, what contaminants are not in the herb, and what the primary compounds are.

-

How to grow

Motherwort is a perennial wildflower, which means it can easily become established if grown in the correct conditions. It can be grown in full sunshine or partial shade in any soil type although it prefers moist, rich soil with a slightly alkaline pH.

Plants can be propagated from seed in autumn or spring. Sow indoors in pots or trays in late winter or early spring. To sow in late spring or early summer use the cold stratification method by keeping the seeds refrigerated for a few weeks.

Once the cold stratification time has passed, sow indoors in pots or trays in late winter or early spring. Keep the compost moist as germination can take a few weeks.

Once the plants are big enough to handle they can be transferred into small pots or planted out in the summer. Motherwort will self seed easily.

It prefers a damp soil, but waterlogging should be avoided. Generally speaking it is a resilient plant that will be fine in most UK gardens and only needs watering when it is very dry. Once established, this plant is resistant to drought (16).

-

Recipe

Heart calm tea

This heart calm tea is a supportive blend designed to nourish both the physical and emotional heart.

Ingredients

- 30 g dried limeflower

- 30 g dried hawthorn flower

- 25 g dried rose petals

- 15 g dried motherwort

Method

- Blend all the ingredients together in a pot or mixing bowl.

- Boil the kettle.

- Take 2–3 teaspoons of the dried herb mixture and place into a teapot.

- Pour the boiling water into the teapot and let the infusion steep for five minutes. Cover the teapot with a lid to retain the volatile oils from the infusion.

- Drink 2–3 cups per day to uplift mood and nourish the heart.

-

References

- Thomsen M. Phytotherapy Desk Reference. 6th ed. Aeon Books; 2022.

- Fisher C. Materia Medica of Western Herbs. Aeon Books; 2018.

- Mcintyre A. Complete Herbal Tutor : The Definitive Guide to the Principles and Practices of Herbal Medicine (Second Edition). Aeon Books Limited; 2019.

- Holmes P. The Energetics of Western Herbs: : A Materia Medica Integrating Western and Chinese Herbal Therapeutics. Snow lotus press; 2020.

- Wood M. The Earthwise Herbal : A Complete Guide to Old World Medicinal Plants. North Atlantic Books; 2008.

- Bone K, Mills S. Principles and Practice of Phytotherapy: Modern Herbal Medicine. 2nd ed. Edinburgh Churchill Livingstone, Elsevier; 2013.

- Shikov AN, Pozharitskaya ON, Makarov VG, Demchenko DV, Shikh EV. Effect of Leonurus cardiaca oil extract in patients with arterial hypertension accompanied by anxiety and sleep disorders. Phytotherapy Research. 2010;25(4):540-543. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.3292

- Hoffmann D. Medical Herbalism : The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Healing Arts Press; 2003.

- Chen W, Yu J, Tao H, Cai Y, Li Y, Sun X. Motherwort injection for preventing postpartum hemorrhage in pregnant women with cesarean section: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Evidence-Based Medicine. 2018;11(4):252-260. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12300

- Beik A, Joukar S, Najafipour H. A review on plants and herbal components with antiarrhythmic activities and their interaction with current cardiac drugs. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine. 2020;10(3):275-287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcme.2020.03.002

- Natural Medicines. Motherwort. naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Published 2024. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com/databases/food

- RHS. Leonurus cardiaca | motherwort Herbaceous Perennial/RHS. Rhs.org.uk. Published 2025. Accessed February 9, 2025. https://www.rhs.org.uk/plants/9940/leonurus-cardiaca/details

- Royal Botanical Gardens Kew. Leonurus cardiaca L. | Plants of the World Online | Kew Science. Plants of the World Online. Published 2025. https://powo.science.kew.org/taxon/urn:lsid:ipni.org:names:449168-1

- Khela S. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Leonurus cardiaca. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Published May 14, 2013. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/203246/2762562

- Sun J, Wang Y, Garran TA, et al. Heterogeneous Genetic Diversity Estimation of a Promising Domestication Medicinal Motherwort Leonurus Cardiaca Based on Chloroplast Genome Resources. Frontiers in Genetics. 2021;12. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.721022

- Buckner H. How to Grow and Use Motherwort | Gardener’s Path. Gardener’s Path. Published April 30, 2020. https://gardenerspath.com/plants/herbs/grow-motherwort/