-

How does it feel?

-

What can I use it for?

This is a poisonous plant and thus in the UK it is legally restricted for use only by qualified herbalists and medical doctors.

This is a poisonous plant and thus in the UK it is legally restricted for use only by qualified herbalists and medical doctors.It acts on the autonomic portion of the nervous system and is used for the relief of spasms, in particular within the urinary tract but also of use in cases of colic within the digestive tract and for bronchial spasm within the respiratory tract. It has been used in excessive salivation and tremor such as in Parkinson’s disease.

The alkaloid hyoscine is used widely in conventional medicine in various formulations including for spasms in the gut, for nausea, an overactive urinary bladder, as a pre-operative medicine and in palliative care for excessive respiratory secretions or bowel colic.

-

Into the heart of henbane

The tropane alkaloids within henbane and other members of the Solanaceae (Nightshade) family such as Datura and Belladonna have an anticholinergic effect on the nervous system – in other words they dampen down the activity of the parasympathetic portion of the autonomic nervous system, which activates and monitors those involuntary activities that take place within the body such as heart and breathing rate, blood pressure, digestion and urination. Hence this plant’s traditional and modern day use for relaxing acute spasm and for the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease.

-

Traditional uses

Henbane has a long history of use across our herbal medicine traditions. It was often used as an anaesthetic, analgesic, spasmolytic or sedative and was sometimes given to women in childbirth in combination with opium poppy to bring relief in the form of a ‘twilight sleep’ a practice noted on records from Wiltshire (5).

Henbane has a long history of use across our herbal medicine traditions. It was often used as an anaesthetic, analgesic, spasmolytic or sedative and was sometimes given to women in childbirth in combination with opium poppy to bring relief in the form of a ‘twilight sleep’ a practice noted on records from Wiltshire (5).Pain-relieving necklaces were made from the root and placed around the necks of children to ease teething or prevent fitting (5).

Henbane was one of the plants used in soporific sponges or spongia somnifera and pomanders or ‘sleeping apples’ used prior to anaesthesia back in the Middle Ages (6).

In Tibetan medicine the seeds have been used as a remedy against intestinal worms, tumours, toothache and inflammation of the lungs (7).

A paste of the seeds is used in Ayurvedic medicine to be applied over painful joints, including for gout and also for neuralgic or dental pain. It is also prescribed for tremor in cases of Parkinson’s disease and for spasm within the smooth muscle.

It has a tradition of use traceable back to the Babylonians and a long association with soothsaying, witchcraft and magic.

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Western energetics

-

What practitioners say

Henbane (Hyoscyamus niger) Caution is key, and practitioners will only ever use such a herb if no other will suffice. Drop doses of this herb are usual and are prescribed when such circumstances arise, with a very gradual increase if required and never exceeding a maximum daily dose.

Digestive system

Henbane can be a valuable remedy for severe spasm in the gut where other, milder herbs may not be as effective, including for use in biliary colic(gall bladder spasm). It can significantly slow down the transit time of the gut and reduce the secretory ability so has sometimes been used in cramping associated with severe bouts of diarrhoea.

Respiratory system

Datura is sometimes thought to be more indicated for asthma, however henbane is also useful here and can also be helpful in cases of whooping cough.

Nervous system

Henbane can be indicated in Parkinson’s disease, for use in tremors or excessive salivation. In Ayurvedic medicine it is often used in a combination therapy for this condition (8). It is also of use in neuralgia and myalgia and can help with the symptoms of Meniere’s disease and motion sickness.

Externally

It has been used topically in the form of an oil for neuralgia including sciatic pain and myalgia and gout.

-

Research

The different alkaloids have slightly different properties, however as a whole, henbane inhibits the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine and thus has a dampening down effect on the parasympathetic portion of the autonomic nervous system. Henbane causes a decrease in sweat, salivary, gastric and bronchial secretions, lessens the tone and motility of smooth muscle in the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts and increases the pulse rate.

The different alkaloids have slightly different properties, however as a whole, henbane inhibits the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine and thus has a dampening down effect on the parasympathetic portion of the autonomic nervous system. Henbane causes a decrease in sweat, salivary, gastric and bronchial secretions, lessens the tone and motility of smooth muscle in the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts and increases the pulse rate.There is a paucity of quality human trials data on henbane however, a recent small randomised clinical trial was carried out on the effects of propolis combined with henbane for clinical symptoms in patients with acute respiratory syndrome associated with Covid-19. The formulation was given to 50 patients of mixed sex between the ages of 18 and 75 in the form of a syrup. A significant improvement was observed in the intervention group on a number of symptoms including reduction of cough, shortness of breath and chest pain, compared to those on placebo. These improvements became more pronounced with the increasing number of days of treatment. These initial findings are promising and call for larger studies (9).

-

Did you know?

The genus name Hyoscyamus comes from the Greek hyoskyamos, – hys meaning pig and kyamos meaning bean. Hog bean is also one of the herb’s common names, perhaps because pigs can eat henbane without being poisoned, although other livestock don’t have this protection.

The genus name Hyoscyamus comes from the Greek hyoskyamos, – hys meaning pig and kyamos meaning bean. Hog bean is also one of the herb’s common names, perhaps because pigs can eat henbane without being poisoned, although other livestock don’t have this protection.Gerard the herbalist (1545-1612) says of henbane: ‘The leaves, the seeds and the juice when taken internally cause an unquiet sleep, like unto the sleep of drunkeness, which continueth long and is deadly to the patient. To wash the feet in a decoction of henbane, as also the often smelling of the flowers causeth sleep’ – referring to the potency of the plant, which can exert such effects even via the skin and respiratory system.’

In the middle ages it was known as ‘Witches herb’, being made into an ointment along with other alkaloid-containing herbs and applied topically, giving the hallucinatory sensations of flying and bypassing the digestive tract to afford being able to take higher doses, although still very much risking death!

This anonymous individual summarised the danger of messing with Henbane: ‘If it be used in sallet (salad) or in pottage (soup/stew), then it doth bring frenzie, and whoso useth more than four leaves shall be in danger to sleepe without waking’.

Additional information

-

Botanical description

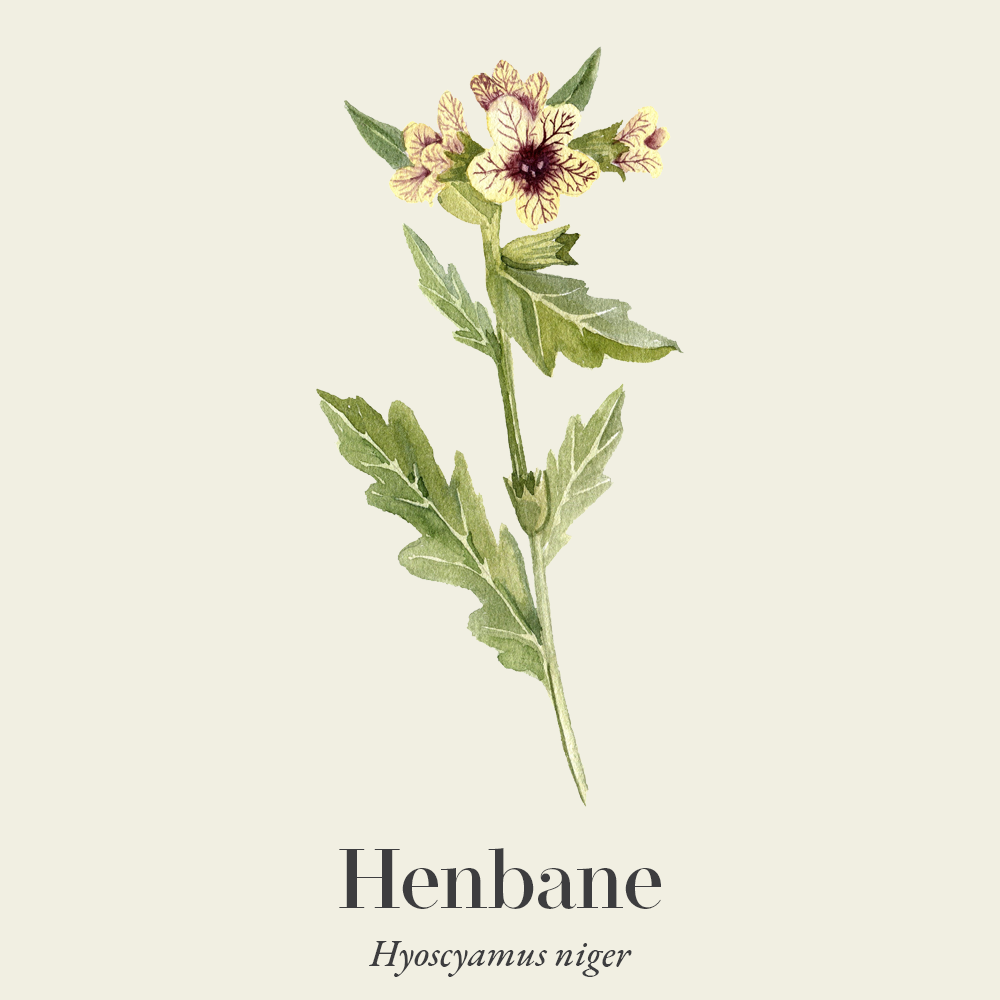

This striking-looking plant is one of 15 species within the Hyoscyamus genus. A member of the Solanaceae family to which belong tomatoes, tobacco, potatoes, peppers, aubergines and the medicinal members Deadly nightshade and Datura. There are annual and biennial forms of henbane, the biennial being thought to be superior for medicinal use (1). It can grow up to a height of around a metre. Thought to be native of a broad region of Eurasia, it has naturalised in many regions globally and whilst not considered a common plant, it has a reputation as a noxious weed in North America. It prefers disturbed or cultivated habitats but also thrives in wild coastal areas and relishes hot summers (2).

Henbane has pale green, coarsely-toothed leaves up to 30 cm long and burgundy-veined, creamy-yellow bell-shaped flowers, with a deep burgundy throat that appear from spring to autumn. The fruit is described as pyxis in shape – an urn-shaped capsule with a lid-like top that when opens spills the seeds. It has a certain sinister beauty about it. The entire plant is hairy, sticky and has a strong and unpleasant odour to entice the blowflies that are its main pollinators.

The fresh or dried leaves or flowering tops are used medicinally, occasionally the seeds.

-

Common names

- Henbane

- Hogbean

- Jupiter’s bean

- Devil’s eye

- Stinking nightshade

-

Safety

This herb is a poison. In the UK it falls under the legislation for Human Use Regulations 2012 within the schedule 20 part 2 herbs. This means that it is a practitioner-only medicine and has clear maximum weekly and single doses (10). The reason for this is that it has a narrow therapeutic window, (the effective therapeutic dose is close to the poisonous one).

Symptoms of over-dosage can start with a dry mouth, dry skin, dilated pupils, warm, flushed skin and agitation, going on to include impaired vision, delirium, hallucinations, convulsions and coma. It can cause death from heart or respiratory failure. Definitely not a plant to mess with.

It is certainly contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation and also in glaucoma, tachycardic arrythmia (rapid heart rate), and urinary retention.

As henbane is classed as a restricted herb within UK legislation it can only be prescribed following a one-to-one consultation with a qualified practitioner. x In many countries the use of henbane is illegal.

-

Dosage

Maximum weekly dose is 20 ml of a 1:10 tincture

Maximum single dose: 100mg

Maximum daily dose: 300mg

Practitioners start low and only slowly work upwards if required, in drop doses whilst monitoring closely. Effects can vary between individuals.

-

Constituents

- Tropane alkaloids: principally hyoscyamine, hyoscine (scopolamine), atropine

- Flavone glycosides: quercetrin, rutin, Kaempferol

- Volatile amines: choline, methylpyrroline pyridine (3,4)

-

References

- Grieve, M (1931): A Modern Herbal. Tiger press. Ed 1992. ISBN 1-83-5501-249-9

- Mitchhttps://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/28251#todescription

- Gjafarzadegan, R et al. (2010): Optimization of extraction method of Hyoscine from Hyoscyamus niger. Journal of Medicinal plants, 9 (36): 87-95

- BHMA British Herbal Compendium Vol 1.(1992).ISBN 0 903032 09 0

- Allen, D and Hatfield G: Medicinal plants in folk tradition. An ethnobotany of Britain and Ireland. (2004) Timber Press. ISBN 0 88192 638 8

- Holzman, R. (1998) The legacy of Atropos, the fate who cut the thread of life. Anaethesiology. Vol 89, 241-249.

- Tsarong. Tsewang. J. Tibetan Medicinal Plants Tibetan Medical Publications, India 1994 ISBN 81-900489-0-2

- Banjari, I et al. (2018): Forestalling the epidemics of Parkinson’s disease through plant-based remedies. Frontiers in Nutrition. Doi 10.3389/fruit.2018.00095

- Kosari, M et al. (2021) The effects of propolis plus Hyoscyamus niger L. methanolic extract on clinical symptoms in patients with acute respiratory syndrome suspected to Covid-19: A clinical trial. Phytotherapy Research. https://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.7116 accessed 21.5.21

- https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/list-of-banned-or-restricted-herbal-ingredients-for-medicinal-use/banned-and-restricted-herbal-ingredients. Accessed 9.5.21

This is a poisonous plant and thus in the UK it is legally restricted for use only by qualified herbalists and medical doctors.

This is a poisonous plant and thus in the UK it is legally restricted for use only by qualified herbalists and medical doctors. Henbane has a long history of use across our herbal medicine traditions. It was often used as an anaesthetic, analgesic, spasmolytic or sedative and was sometimes given to women in childbirth in combination with opium poppy to bring relief in the form of a ‘twilight sleep’ a practice noted on records from Wiltshire (5).

Henbane has a long history of use across our herbal medicine traditions. It was often used as an anaesthetic, analgesic, spasmolytic or sedative and was sometimes given to women in childbirth in combination with opium poppy to bring relief in the form of a ‘twilight sleep’ a practice noted on records from Wiltshire (5). The different alkaloids have slightly different properties, however as a whole, henbane inhibits the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine and thus has a dampening down effect on the parasympathetic portion of the autonomic nervous system. Henbane causes a decrease in sweat, salivary, gastric and bronchial secretions, lessens the tone and motility of smooth muscle in the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts and increases the pulse rate.

The different alkaloids have slightly different properties, however as a whole, henbane inhibits the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine and thus has a dampening down effect on the parasympathetic portion of the autonomic nervous system. Henbane causes a decrease in sweat, salivary, gastric and bronchial secretions, lessens the tone and motility of smooth muscle in the urinary and gastrointestinal tracts and increases the pulse rate. The genus name Hyoscyamus comes from the Greek hyoskyamos, – hys meaning pig and kyamos meaning bean. Hog bean is also one of the herb’s common names, perhaps because pigs can eat henbane without being poisoned, although other livestock don’t have this protection.

The genus name Hyoscyamus comes from the Greek hyoskyamos, – hys meaning pig and kyamos meaning bean. Hog bean is also one of the herb’s common names, perhaps because pigs can eat henbane without being poisoned, although other livestock don’t have this protection.