-

How does it feel?

Probably the simplest way to sample ginseng is to obtain a good quality tablet of the dried root powder, This can easily and safely be chewed. There is a faint fragrant aroma and then the main impression is of gentle sweetness, for most a quite pleasant taste. There is a definite mucilaginous quality as the powder is moistened in the mouth (this is due to the soapy properties of the saponins that are the main actives in ginseng) and finally a mild bitter aftertaste.

The consistent reputation of ginseng is as a tonic and as is seen here this is linked to both the traditional medicinal qualities of (subtle) sweetness and to the properties of saponins, that are so often linked to benefits on the body’s steroid metabolism.

-

What can I use it for?

The traditional use of ginseng, partially supported by clinical trial evidence, is to improve mental performance and well-being, and particularly to improve stress responses.

It has long been used as a tonic when rundown and exhausted, and for the elderly and infirm.

It has a particular tradition in helping men with prostatic problems and also those with poor sexual performance.

There is clinical evidence that it can be helpful in low-grade circulatory problems and non-insulin dependent Type 2 diabetes.

-

Into the heart of ginseng

Panax or red ginseng was in the 1950’s the first defined ‘adaptogen’, described as a remedy that could improve the body’s capacity to cope with (‘adapt to’) stressful circumstances. It has been widely used to increase strength and endurance during periods of short-term and long-term stress.

Panax or red ginseng was in the 1950’s the first defined ‘adaptogen’, described as a remedy that could improve the body’s capacity to cope with (‘adapt to’) stressful circumstances. It has been widely used to increase strength and endurance during periods of short-term and long-term stress.In The Root of Being: the Pharmacology of Harmony, an influential book published in 1980, Stephen Fulder argued that ginseng’s benefits could be due to its ability to modulate the responses of the adrenal cortex to stress. This gland produces steroid hormones and Fulder made the case that as ginseng contains steroidal-like substances (ginsenosides) it could interact with the body’s switching mechanisms, particularly in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal cortex axis. This could explain the use of ginseng both to switch on protective responses at the onset of stress, and to avoid adrenal exhaustion by switching them off more effectively when they had done their job. It has been used for this benefit by soldiers, cosmonauts and students studying for exams.

This short term effect is one of two quite separate traditional uses for ginseng. The second was as a long-term remedy for people who are rundown, tired, recovering from illness or injury, or more generally infirm.

-

Traditional uses

Ginseng is classified in traditional Chinese medicine as a qi tonic. Such tonics are used to support active (yang) energies and are used for depletion of qi, particularly in the Chinese Spleen and Lungs.

Ginseng is classified in traditional Chinese medicine as a qi tonic. Such tonics are used to support active (yang) energies and are used for depletion of qi, particularly in the Chinese Spleen and Lungs.In the case of deficient Spleen qi, possibly as a result of prolonged illness or constitutional weakness, disturbance is likely to affect the functions of assimilation and distribution, to be associated with such symptoms as fatigue and depression with depressed digestion, diarrhoea, abdominal pain or tension, visceral prolapse, pale yellow complexion with a tinge of red or purple, pale tongue with white coating, and/or languid, frail or indistinct pulses. This may lead in turn to a “damp” condition developing.

In the case of deficient Lung qi, extreme or prolonged stress or disease, or chronic pulmonary disease, leads to depletion or cold in the Lungs, with easy fatigue and prostration associated with disturbances of regulation, shortness of breath or shallow breathing, rapid, slow or little speech, spontaneous perspiration, pallid complexion, dry skin, pale tongue with thin white coating, weak and depleted pulses. Its primary use here in acute medicine was for conditions marked by shallow respiration and shortness of breath.

Ginseng also benefits and calms the Spirit (a manifestation of Heart qi – hence is used for palpitations with anxiety, insomnia and restlessness). In the west ginseng had a range of uses. In 20th century British herbalism is was applied to the treatment of neurasthenia (exhausted nervous conditions), neuralgia and for depressive states, particularly associated with depleted libido. In 19th century North America the Eclectic physicians used it in addition for asthma and convulsions.

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Chinese energetics

Western energetics

-

What practitioners say

Adrenals

AdrenalsAs an adaptogen ginseng can support prompt stress management while also protecting against exhaustion. Adaptogens improve overall wellbeing, increase energy, increase inner strength, improve libido, balance the stress response, improve blood sugar levels, optimise protein synthesis, reduce inflammatory cortisol levels and optimise the function of all of your organs.

Musculoskeletal

Ginseng is indicated for the very active as well as the elderly. It has been used to improve muscle regeneration and repair after exertion.

Nervous

Ginseng supports a nervous system that has become weakened by stress. It is indicated in states of nervous insomnia, prolonged anxiety, depression and chronic fatigue syndrome. It is not a stimulant as such although in some cases has been used with, and then exacerbated other stimulants.

Cardiovascular

Ginseng tonifies the heart and improves cardiac performance. There is evidence that it reduces various inflammatory markers and benefits several conditions linked by endothelial dysfunction: hypertension, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes, and can reduce blood cholesterol and lipid levels.

-

Research

In a systematic review of the clinical evidence ginseng was shown to be a promising treatment for fatigue, especially in people with chronic illness. However this review confirmed the widespread observation that the evidence base for ginseng is notably mixed and called for more robust studies (1).

In a systematic review of the clinical evidence ginseng was shown to be a promising treatment for fatigue, especially in people with chronic illness. However this review confirmed the widespread observation that the evidence base for ginseng is notably mixed and called for more robust studies (1).There is encouraging evidence that ginseng can benefit men with erectile dysfunction, although the meta-analysis concluded that more robust studies are required (2). Ginseng has sometimes been regarded as a male remedy in Asian cultures and the evidence so far does not support its benefits in symptoms of the female menopause (3).

There are a number of studies that point to the benefits of ginseng on markers of inflammation, circulatory disease and metabolic problems (all tentatively linked by endothelial dysfunction). One meta-analysis and systematic review concluded that ginseng improved glucose control and insulin sensitivity in patients with Type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose intolerance (4). A similar tentative conclusion had earlier been reached (5). In a meta-analysis of clinical trials a significant effect was demonstrated for the effect of ginseng on blood levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), a standard marker of inflammatory activity in the body (6). Another review has shown collected benefits on cholesterol and blood lipid levels (7), and similar guarded benefits have been shown in the reduction of high blood pressure (8,9).

-

Did you know?

In former imperial China the social ranking of court officials would be marked by the splendour of the ginseng root that they could afford for their retirement. The most valuable were not only the largest but those most man-shaped. Each root would be displayed in a glass jar and steeped in wine. A daily sip would be taken and the wine replenished. This way the root could provide tonic strength long into a healthy old age.

Additional information

-

Botanical description

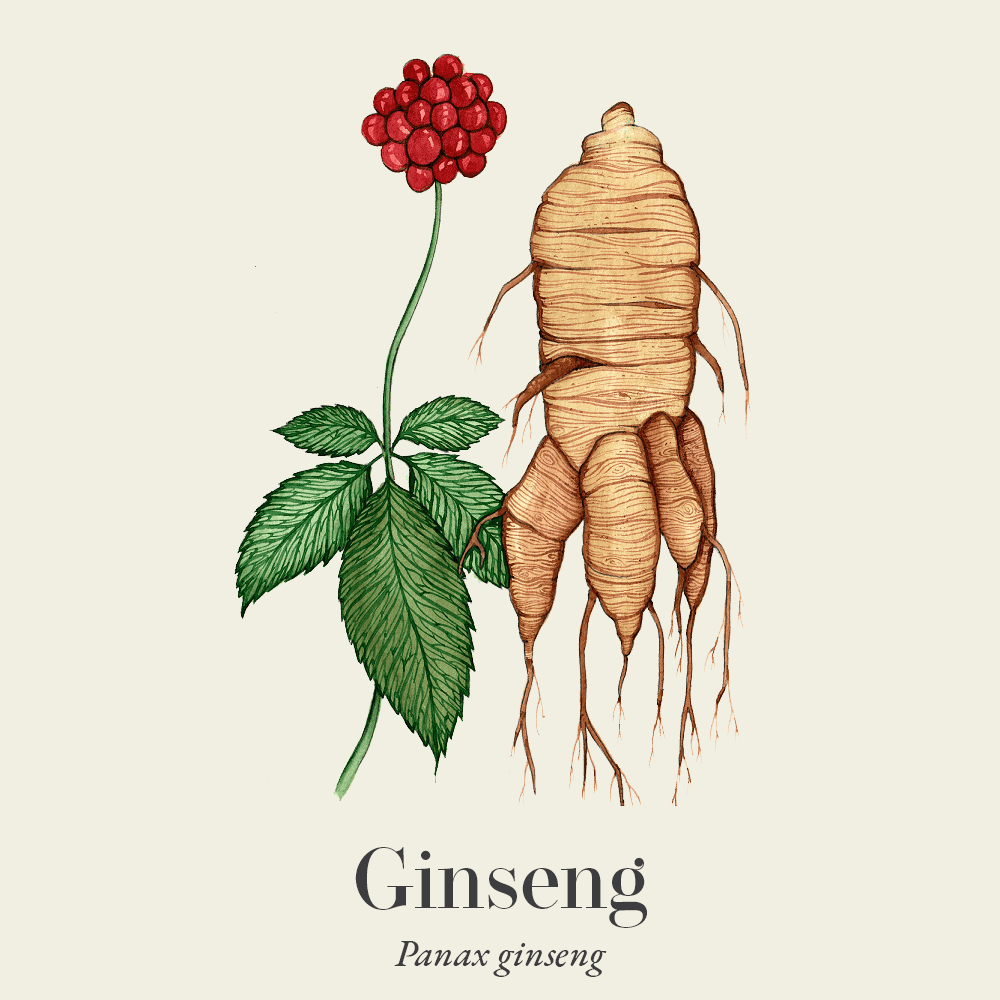

Panax ginseng is a perennial slow-growing herb native to the mountainous regions of China, Japan, Korea and Russia, though now extremely rare in the wild. The stem is erect, simple not branching, the leaves are verticillate and compound with five leaflets; the three terminal leaflets are larger than the lateral ones. The flowerhead is a small umbel consisting of pink flowers with five petals. The fruit is a small berry which is red when ripe. The pale yellow/brown roots grow up to 10cm and characteristically represent the shape of the human form (‘man root’). The material used commercially is entirely from cultivated plants as Panax ginseng is a grade-II listed species on China’s Protected species list, requiring harvesting and trade to take place only with a permit from provincial authorities and under their oversight.

The root is sometimes cured soon after harvesting, a process involving steaming, sun-drying and smoking, this producing so-called “red ginseng”, a deep-red root with a glassy fracture.

Alternate botanical names:

There are many species of ginseng recorded, notably the American ginseng P. quinquefolium L, P. pseudo-ginseng var. notoginseng Burk., found wild in the Yunnan and Kwangsi provinces of China, and P. pseudo-ginseng var. japonicus C.A. Meyer., or Japanese ginseng. There is also a distantly related “Siberian ginseng”, Eleutherococcus senticosus. All these plants have different constituents and activities and only P. ginseng is discussed here.

-

Common names

- Asiatic ginseng

- Red ginseng

- Man root (Eng)

- Ginsengwurzel (Ger)

- Kraftwurzel (Ger)

- Racine de ginseng (Fr)

- Ren shen (Chin)

- Ninjin (Jap)

- Insam (Kor)

-

Safety

Ginseng is safe to take. ‘Ginseng abuse syndrome’ was reported in the USA during the 1980’s. The notion that ginseng could induce irritability, anxiety and restlessness did not survive an era when overdosing was common, and particularly mixing with high levels of caffeine and other stimulants.

-

Dosage

Practical use in the west suggests a daily dose of 1-3 grams for short term use (for up to 14 days), with a longer term regime of 0.5-0.8 grams daily

-

Constituents

- triterpenoid saponins ginsenosides Rb, Rg and Rc

- panax acid, glycosides (panaxin, panaquilin, ginsenin)

- beta-sitosterol, stigmasterol, campesterol

- a sesquiterpene (pancene)

- polyacetylenes (alpha-elemene, panaxynol), kaempferol, choline, essential oil.

There are many ginsenosides so far described, generally divided into groups based on two dammarine-type core triterpenes called protopanaxadiol and protopanaxatriol, called for this reason “diols” and “triols” (ginsenosides Rb and Rc are diols, ginsenoside Rg is a triol). Most research interest has focused on the “triol” group which have been found to be the most stimulating, the “diols” being more sedative. (diols predominate in the American ginseng, Panax quinquefolium).

-

Recipe

Winter Tonic Elixir

This is a fun and easy-to-make ‘winter tonic elixir’ with a mix of herbs that raise your energy and warm you to the core.

Ingredients

- Brandy 700ml/25fl oz

- Amaretto 300ml/10fl oz

- Ginseng root 20g/3/4oz

- Astragalus 10g/1/3oz

- Cinnamon bark 10g (about 2 quills)

- Ashwagandha 5g

- Ginger root powder 5g

- Rosemary 2 sprigs

- Orange peel 5g

This makes 1 litre/35fl oz of tasty tincture.

Method

- Blend the liquids and soak the herbs in it for 1 month and then strain. Bottle half for you and half for a friend.

- Sip on cold winter nights to raise your spirits and keep you strong.

Recipe from Cleanse, Nurture, Restore by Sebastian Pole

-

References

- Arring NM, Millstine D, Marks LA, Nail LM. (2018) Ginseng as a Treatment for Fatigue: A Systematic Review. J Altern Complement Med. 24(7): 624–633

- Borrelli F, Colalto C, Delfino DV, et al. (2018) Herbal Dietary Supplements for Erectile Dysfunction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Drugs. 78(6): 643–673

- Lee HW, Choi J, Lee Y, et al. (2016) Ginseng for managing menopausal woman’s health: A systematic review of double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Medicine (Baltimore). 95(38): e4914

- Gui QF, Xu ZR, Xu KY, Yang YM. (2016) The Efficacy of Ginseng-Related Therapies in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 95(6): e2584

- Shishtar E, Sievenpiper JL, Djedovic V, et al. (2014) The effect of ginseng (the genus panax) on glycemic control: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. PLoS One. 9(9): e107391

- Saboori S, Falahi E, Yousefi Rad E, et al. (2019) Effects of ginseng on C-reactive protein level: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Complement Ther Med. 45: 98–103

- Hernández-García D, Granado-Serrano AB, Martín-Gari M, et al. (2019) Efficacy of Panax ginseng supplementation on blood lipid profile. A meta-analysis and systematic review of clinical randomized trials. J Ethnopharmacol. 243: 112090

- Lee HW, Lim HJ, Jun JH, Choi J, Lee MS. (2017) Ginseng for Treating Hypertension: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Double Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trials. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 15(6): 549–556

- Komishon AM, Shishtar E, Ha V, et al. (2016) The effect of ginseng (genus Panax) on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. J Hum Hypertens. 30(10): 619–626

Panax or red ginseng was in the 1950’s the first defined ‘adaptogen’, described as a remedy that could improve the body’s capacity to cope with (‘adapt to’) stressful circumstances. It has been widely used to increase strength and endurance during periods of short-term and long-term stress.

Panax or red ginseng was in the 1950’s the first defined ‘adaptogen’, described as a remedy that could improve the body’s capacity to cope with (‘adapt to’) stressful circumstances. It has been widely used to increase strength and endurance during periods of short-term and long-term stress. Ginseng is classified in traditional Chinese medicine as a qi tonic. Such tonics are used to support active (yang) energies and are used for depletion of qi, particularly in the Chinese Spleen and Lungs.

Ginseng is classified in traditional Chinese medicine as a qi tonic. Such tonics are used to support active (yang) energies and are used for depletion of qi, particularly in the Chinese Spleen and Lungs. Adrenals

Adrenals In a systematic review of the clinical evidence ginseng was shown to be a promising treatment for fatigue, especially in people with chronic illness. However this review confirmed the widespread observation that the evidence base for ginseng is notably mixed and called for more robust studies (1).

In a systematic review of the clinical evidence ginseng was shown to be a promising treatment for fatigue, especially in people with chronic illness. However this review confirmed the widespread observation that the evidence base for ginseng is notably mixed and called for more robust studies (1).