-

How does it feel?

-

What can I use it for?

Chaga (Inonotus obliquus) Chaga can be used safely within the correct range of dosage to support the health of the cardiovascular system, digestive system and for metabolic health. Chaga is a medicinal fungus that has become widely known for its high levels of antioxidant potential. Antioxidants are used to protect cells against damage from free radicals and have a number of other important activities in the body. Antioxidants play an important role in protecting us against heart disease and cellular abnormalities, such as cancer (1, 2, 3)

Chaga has powerful antioxidant properties and it is also understood to have anti-aging and immunomodulatory effects (4, 5). Chaga can be taken as a daily tonic to help support the health of our digestive system, particularly for intestinal health (6).

Regular intake of chaga has many potential health benefits, particularly in relation to metabolism. It contains compounds called beta-D-glucans which have been shown to help lower blood sugar levels as well as to help regulate the immune system (4).

Chaga’s medicinal compounds are best extracted with heat. It is most commonly drank as a decocted tea (see dosage for instructions). The resulting decoction can also be blended into smoothies, broths and hot drinks like cacao or hot chocolate. Chaga is also suitable to use in culinary recipes such as in stews or slow cooked meals.

-

Into the heart of chaga

Chaga (Inonotus obliquus) Energetically, chaga is classified as warm and sweet. On a cellular level, chaga provides cell support and protection, owing to its cytoprotective properties (4, 5). It also moderates the immune system in a number of ways making it a choice medicine where there is systemic inflammation and depletion. Chaga has been used traditionally to treat fatigue and convalescence (1, 3).

In traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) chaga is used to treat the heart shen — heart shen relates to the mind and spirit where emotional and creative functions are concerned — as it is said too to harmonise the spirit. It is also understood to support cognitive function, memory and concentration. Where the liver, spleen, heart, kidneys, stomach channels are indicated, chaga may be applied. It nourishes the liver, kidneys and heart. Chaga is also understood to revive the blood, calm the mind and increase qi (life force or vitality).

Chaga is a tonic to the digestive tract (3) that is thought to protect the gastric mucosa and it may be useful for the treatment of gastritis and ulcers (4). Chaga also supports the vital functions of the liver via its hepatoprotective action (3).

-

Traditional uses

Chaga (Inonotus obliquus) Chaga has been used as a folk medicine in various cultures around the globe. Accounts of its use in Europe, especially in Russia, Poland and the Baltic countries as a remedy for gastritis, ulcers and cancer are particularly present (6).

In Russia and Siberia, chaga was taken as a strong decoction or tea to improve general health, increase vitality and to prevent illness and infection (8). Here, chaga has long-standing use as a remedy for fatigue and to assist in the convalescence stages of illness and was also traditionally esteemed for treating a variety of cancers (1, 3). For more insights on integrative cancer care and mushrooms, see our article “Mushrooms for cancer care“.

One of the oldest references to the use of chaga as a medicine is by Hippocrates (c.460–370 BCE) in his Corpus Hippocraticum where chaga was referenced for use in the form of infusions to wash wounds (7).

In TCM chaga was used to support metabolic function, cardiovascular health, and for its antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activities (4).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Western energetics

Chinese energetics

-

What practitioners say

Chaga (Inonotus obliquus) Cardiovascular system

Herbalists may use chaga for a wide range of conditions in the cardiovascular system. Chaga has a number of therapeutic actions that make it beneficial to the heart and vasculature such as its antioxidant, immune-boosting, anti-inflammatory, and adaptogenic effects. It may be used as part of an approach to treat heart disease, high cholesterol, hypertension, hyperglycemia (high blood sugar) and atherosclerosis (4).

Digestive system

In Europe, chaga has been traditionally used for a number of conditions in the digestive system, particularly where there is chronic inflammation. Chaga’s use in the treatment of ulcers and gastritis (4) correlates with promising research around its antioxidant effects in the lower digestive system.

This study shows that chaga reduces oxidative stress in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). As reduced antioxidant levels have been implicated in the cause of IBD, chaga shows promise as a treatment approach to modulate free radical concentrations to improve such conditions (8).

The regenerative effect of chaga on the tissues is also owing to its antioxidant action. Interestingly, in Russia a decoction of chaga is traditionally used as a colonic treatment to target the lower bowel (4).

Immune system

Chaga has been used traditionally in Russian folk medicine for cancers. Chaga has been researched for these effects through laboratory studies which have identified a number of cytotoxic actions (9). In vitro have identified anti-proliferative and proapoptotic effects of chaga extracts. Chaga’s powerful antioxidant action also makes it a highly valuable medicine for the maintenance of cellular health and regeneration (10).

Traditional use of chaga in cancer includes therapy for breast, cervix, and skin cancers (2). There are however limited studies on people, and if one wants integrative oncology care then it is best to work with a specialist as treatment is nuanced and case specific. It may be a beneficial medicine to apply as part of an integrative approach to treating cancer, although it must be noted that human clinical studies are required to identify the true potential of chaga as a support in cancer therapy.

A number of compounds in chaga have demonstrated powerful antioxidant activities. Chaga polysaccharides are active constituents that work by directly inhibiting the progress of the oxidation reaction, thereby blocking the initiation of the lipid peroxidation (5). Chaga polysaccharides also significantly enhance lymphocyte (white blood cell) proliferation as well as showing anti-tumor activity (5).

The antioxidant actions of chaga can be called upon as a prophylactic against the ill effects of free radicals. These effects contribute towards the prevention of a number of serious and chronic diseases that are associated with oxidative stress, such as atherosclerosis, cancer, diabetes, and degenerative diseases of the central nervous system (7). Chaga is also understood to have anti- aging and immunomodulatory effects (11,5).

-

Research

Chaga (Inonotus obliquus) There are a number of in vitro studies that have been carried out to establish the effects of chaga extracts and its bioactive compounds, which show promising results for strengthening the immune system and fighting cancer (6). One clinical study has been included although there are currently a lack of available human studies exploring the known effects of chaga. Double blind, placebo controlled studies offer the greatest insight into the effects of plant and fungi medicines for clinical practice.

Below, a number of studies have been included to elaborate on the mechanistic underpinnings of some of chaga’s medicinal actions discussed in this monograph

In pre-clinical studies, which include both in vivo and in vitro, chaga has demonstrated antitumor, anti-mutagenic, antiviral, antiplatelet, antidiabetic effects. Furthermore, studies have also identified hepatoprotective, antioxidant, analgesic, immunomodulating, anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving actions (5). Chaga polysaccharides have been shown to increase exercise endurance and biological measures related to fatigue (3). More clinical studies would help to ascertain the relevance of these findings in relation to human subjects.

Chaga mushroom extract inhibits oxidative DNA damage in lymphocytes of patients with inflammatory bowel disease

Oxidative stress from free radicals and reduced antioxidant levels are understood to contribute to the cause of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). This study set out to induce oxidative stress and DNA damage using hydrogen peroxide in vitro on peripheral lymphocytes obtained from 20 IBD patients and 20 healthy subjects.

An ethanolic extract of chaga mushroom was used as a protective antioxidant. DNA damage was assessed in 50 cells per individual, making 1000 observations per experimental point. The study demonstrates that chaga extract attenuated induced DNA damage within the patient group. Lymphocytes from Crohn’s disease patients had a greater basic DNA damage than ulcerative colitis patients. The study concludes that chaga extract reduces oxidative stress when challenged in vitro in lymphocytes from IBD patients and also healthy subjects (8).

Chaga mushroom (Inonotus obliquus) induces G0/G1 arrest and apoptosis in human hepatoma HepG2 cells

An in vitro study was carried out to investigate the anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of chaga mushroom water extract on human hepatoma cell lines, HepG2 and Hep3B cells. The findings suggested that chaga may elicit anticancer activity in the treatment of hepatoma (10).

Chaga mushroom triterpenoids as adjuncts to minimally invasive cancer therapies: A review

A review of in vitro studies was carried out to investigate the effects of chaga triterpenoid extracts as a potential anti-cancer agent. The review findings show a number of mechanisms by which chaga demonstrated anti-cancer activities. Such as antiproliferative and cytotoxic actions. The review also describes these effects to be similar to that of conventional chemotherapy drugs such as 5-fluorouracil with chaga triterpenoids inhibiting cellular changes in human epithelial cells to the same extent (14). These findings should be viewed as preclinical relevance and not as a reflection of true effects of chaga mushroom extracts in practice. For those seeking to support themselves best during cancer treatment it vital to work with an integrative oncology specialist as treatment is nuanced and case specific.

Chaga and psoriasis

Several anecdotal reports indicate benefit of chaga for psoriasis. In Martin Powell’s book Medicinal Mushrooms: A Clinical Guide a Russian study on 50 psoriasis patients is referenced. The study reported a 76% cure rate, with improvement in a further 16% of cases. The study length indicated results at between 9–12 weeks where improvements were said to have been reported (15, 16). However, these findings have not been replicated in any other studies since.

-

Did you know?

One of the earliest references of use for chaga as a medicine was by the Khanty people (one of the indigenous minorities in Siberia) around the 12th century. Their method combined the elements of fire and water to create a potent decoction. In this traditional method chunks of chaga were placed directly into a fire for a period of time.

Once the chaga glowed red with heat it was then removed and placed into hot water to make an alchemical decoction. The extract was used externally to clean and purify after menstruation and birthing. It was also used as a wash to treat sores.

Additional information

-

Botanical description

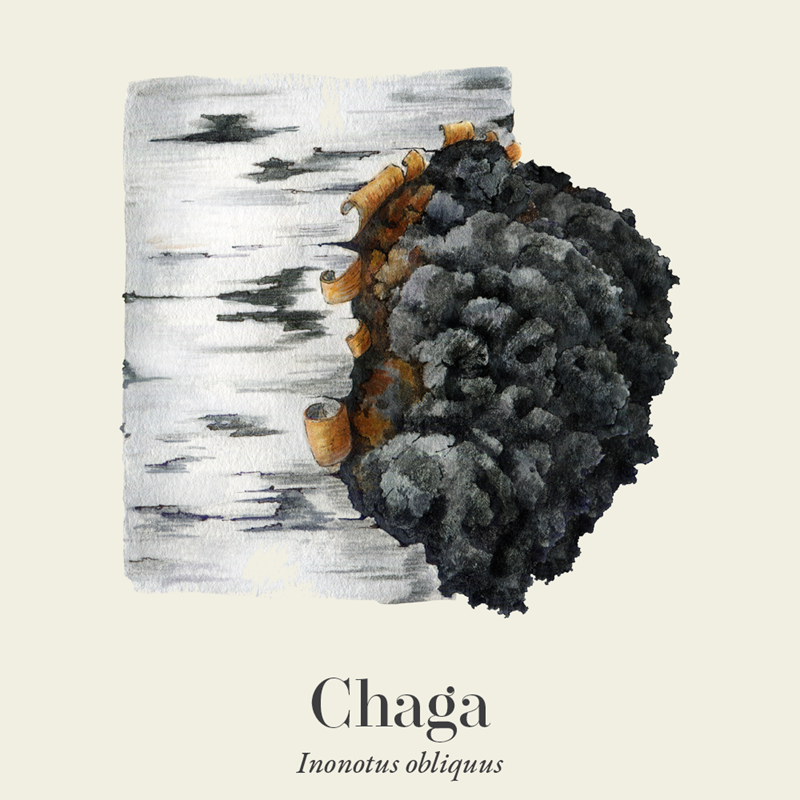

Chaga is a slow-growing parasitic tree fungus found in cold climates around the world. It can usually be found growing on the boles of birch tree. It is less often seen growing on alder, ash, beech, chestnut, hornbeam, plane-tree, poplar, maple, rowan, oak, walnut, and willow. However, reports on the growth of chaga on trees besides birch or beech are often unreliable as the fungus growing on the other kinds of tree are similar and often confused with chaga.

Chaga is usually between 25–40 cm in size. It classically infests trees that are between 30–40 years old through wounds in the bark and can continue to grow on the tree bole for another 30–80 years. On old trees the growth of chaga can exceed 50 cm in diameter.

As it matures, it dries to a consistency similar to that of hard cork. It resembles a lump of burnt, craggy black/ brown coloured charcoal on the outside and when cracked open its inside is a powdery golden/ orange in colour (17).

-

Common names

- Birch conk (a woody growth)

- Clinker polypore

- Cinder conk

- Black mass

- Black birch touchwood

- Birch mushroom

- Crooked schiller-porling

- Bai hua rong / hua jie kong jun (Chinese)

- Kabanoanatake (Japanese)

- Rezavec šikmý (Czech)

-

Safety

Chaga contains high concentrations of oxalates (compounds that are believed to build up in the kidneys when taken in extremely high doses). Prolonged ingestion of high concentrations of oxalates has been associated with renal inflammation, fibrosis and progressive renal failure (6, 13).

There is a case report of oxalate nephropathy associated with ingestion of chaga mushrooms at 4–5 teaspoons per day for 6 months and another case report that associated long-term high dosing of chaga with oxalate nephropathy at a dosage of 10 to 15 g per day for 3 months (6, 13). Both cases presented with complex health histories, with the first undergoing treatment for cancer and the second.

-

Interactions

Chaga may interact with anti-diabetic medications, immunosuppressants and anticoagulants — although these findings are mostly based on anecdotal findings from laboratory and animal studies (3).

It is best to work under the guidance of a qualified medical herbalist, if you are seeking to use herbal medicines alongside other medications or if you have ongoing chronic or complex illnesses.

-

Contraindications

It is recommended to avoid taking chaga close to surgery, as it can slow the rate of blood coagulation (blood clotting) (3).

-

Preparations

Medicinal fungi preparations are often said to be optimised via double extraction methods using — hot water and then alcohol — as this encompasses the majority of desirable constituents, such as polysaccharides (water soluble) and phenolic compounds which best extracted with both alcohol and then hot water (12).

However, traditional practices have used decoctions for millennia and many herbalists trust that water extractions bring about an effective medicinal extract.

Pure powdered chaga should, however, be made via an extraction method that involves heat. The fungi is typically dried in an infrared dehydrator at a specific temperature to maximise the quantity of the bioactive compounds. Powdered material that has not been through an extraction process is ineffective as the active constituents have not been made bioavailable.

In Martin Powell’s book, Medicinal Mushrooms: A Clinical Guide (16), an association is discussed regarding aqueous extracts of chaga for anti-tumour activity. Aqueous extracts are prepared by decoction. However, the level of triterpenes (compounds that are associated with anti-tumour activity) in pure aqueous extracts is low and many practitioners prefer to combine aqueous and ethanolic extracts (16).

-

Dosage

Decoction: To make a decoction place up to 1 g of chaga (powdered, fresh or dried chunks) into one cup of boiling water, simmer gently for between 15–20 minutes. This should be drunk hot twice daily (1).

Powdered mushroom extract: The average dosage for powdered extracts is 1–3g a day (16).

-

Plant parts used

Chaga fruiting body

-

Constituents

Beta-glucans: These are polysaccharides that have immune-modulating effects and may contribute to the antioxidant properties of chaga (11).

Polysaccharides: Chaga contains various polysaccharides, which are long chains of sugar molecules. These compounds are present in many medicinal mushrooms and are implicated in their immune-boosting properties (7, 11).

Phenolic compounds: Chaga is rich in phenolic compounds, such as flavonoids and polyphenols, which are known for their antioxidant properties. These compounds help neutralise harmful free radicals in the body (7, 11).

Melanin: Chaga contains melanin, a pigment that has been found to have antioxidant properties (7, 11).

Triterpenoids: These compounds have anti-inflammatory and antiviral properties (7, 10, 11).

Betulin and betulinic acid: Chaga derived from the birch tree contain betulin and betulinic acid. These compounds have been studied for their potential anticancer properties (11).

It’s important to note that the chemical constituents of chaga can vary depending on factors such as the specific geographic location, where it is harvested, the host tree it grows on, and the extraction methods used.

-

Habitat

The genus Inonotus is widespread in North America, Asia and Europe and comprises around 100 species, represented in Europe by four species, one of which is Inonotus obliquus. It is most commonly found growing on birch trees (17).

-

Sustainability

Chaga is considered to be rare in England and more common in Scotland. It is very slow growing and can take 3–5 years to reach maturity — growing for up to 20 years. It is therefore important to consider harvesting methods in order to preserve the natural growth of chaga and to protect the health of the birch trees on which they grow (18).

Habitat loss and over-harvesting from the wild are two of the biggest threats faced by medicinal plant species. There are an increasing number of well-known herbal medicines at risk of extinction. We must therefore ensure that we source our medicines with sustainability in mind.

The herb supplement industry is growing at a rapid rate and until recent years a vast majority of medicinal plant produce in global trade was of unknown origin. There are some very real and urgent issues surrounding sustainability in the herb industry. These include environmental factors that effect the medicinal viability of herbs, the safety of the habitats that they are taken from, as well as the welfare of workers in the trade.

The botanical supply chain efforts for improved visibility (transparency and traceability) into verifiably sustainable production sites around the world is now certificated through the emergence of credible international voluntary sustainability standards (VSS).

Read our article on Herbal quality & safety: What to know before you buy and Sustainable sourcing of herbs to learn more about what to look for and questions to ask suppliers about sustainability.

-

Quality control

Interest in medicinal mushrooms have risen rapidly in the last decade, and with this it is important to note that adulteration and contamination are not uncommon in the supplement industry. Some mushroom supplements also contain fillers as well as incorrect material — i.e. wrong parts of the mushroom which have no medicinal effects. Due diligence is required to obtain effective mushroom extracts. Some understanding of medicinal fungi extraction methods is also required to ensure you are sourcing supplements that have been made using the correct extraction methods to enable upmost bioavailability.

Herbal medicines are often extremely safe to take, however, it is important to buy herbal medicines from a reputed supplier. Sometimes herbs bought from unreputable sources are contaminated, adulterated or substituted with incorrect plant matter.

Some important markers for quality to look for would be to look for certified organic labelling, ensuring that the correct scientific/botanical name is used and that suppliers can provide information about the source of ingredients used in the product.

A supplier should be able to tell you where the herbs have come from. There is more space for contamination and adulteration when the supply chain is unknown.

-

How to grow

Chaga grows naturally on living trees — predominantly birch trees, however they can also grow on other tree species.

- In order to grow chaga mushrooms, one can acquire chaga mycelial ‘plugs’ which are cultured in a laboratory. These can be sourced online through mycelial specialist suppliers.

- The living tree can be inoculated using 3–4 mycelial plugs by inserting these into small holes drilled into the tree.

- Chaga cultivation requires little management, although it does require a lot of patience as they are very slow growing.

Tip: If inoculating birch with chaga mycelial plugs one could consider combining the process with birch sap harvesting (19).

-

Recipe

To get the best out of your chaga, it is recommended to dry the fungus and later grind it into a powder using a coffee grinder or pestle and mortar. This increases the surface area for extraction, allowing more bioactive compounds to be drawn out from the dried material.

Chaga chai tea

Chaga can be decocted along with a blend of Asian herbs — ginger, cardamom, nutmeg, cinnamon, cloves and black pepper — and hot water. Black tea leaves may also be added. Chai is a favourite daily brew that offers a wide range of health benefits.

Method:

- The best way to brew chai is to use whole dried spices and crush or grind them down a little to release their full aroma. The ground chaga mushroom can be added early on in the brewing process to give optimum time for extraction.

- Once the spices have been crushed a little, they can be placed into a pan with a large cup of water. Gently bring to the boil and then reduce the heat to a simmer keeping the lid on (to preserve all the medicinal volatile oils) for between 15–20 minutes.

- Remove from the heat. If using black tea leaves you can add a tea bag into the pan and brew for a further 1–2 minutes off the heat. Otherwise, strain the residual material out of the decoction and pour into a cup.

- The final step is to place the decoction back on the heat and add milk (nut or dairy). Warm through for a minute or two. Serve with honey, sugar or an alternative sweetener to taste. Drink freely throughout the day.

-

References

- Hobbs, C. (2003). Medicinal mushrooms : an exploration of tradition, healing, and culture. Botanica Press.

- Fordjour, E., Manful, C. F., Javed, R., Galagedara, L. W., Cuss, C. W., Cheema, M., & Thomas, R. (2023). Chaga mushroom: a super-fungus with countless facets and untapped potential. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 14, 1273786. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1273786

- Chaga Mushroom | Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. www.mskcc.org. Published February 20, 2023. https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/integrative-medicine/herbs/chaga-mushroom#:~:text=Oral%20administration%20of%20polysaccharides%20from

- chaga — Herbal Monographs. The Sunlight Experiment. Published May 10, 2020. https://thesunlightexperiment.com/herb/tag/chaga#ref-5

- Lu Y, Jia Y, Xue Z, Li N, Liu J, Chen H. Recent Developments in Inonotus obliquus (Chaga mushroom) Polysaccharides: Isolation, Structural Characteristics, Biological Activities and Application. Polymers. 2021;13(9):1441. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/polym13091441 Contributors, W. E. (n.d.). Health Benefits of Chaga Mushrooms. WebMD.

- Kikuchi Y, Seta K, Ogawa Y, et al. Chaga mushroom-induced oxalate nephropathy. Clinical Nephrology 2014;81(06), 440-444. https://doi.org/10.5414/cn107655

- Shashkina MYa, Shashkin PN, Sergeev AV. Chemical and medicobiological properties of chaga (review). Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 2006;40(10):560-568.

- Szychowski KA, Skóra B, Pomianek T, Gmiński J. Inonotus obliquus – from folk medicine to clinical use. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine. 2021;11(4):293-302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcme.2020.08.003

- Najafzadeh M, Reynolds PD, Baumgartner A, Jerwood D, Anderson D. Chaga mushroom extract inhibits oxidative DNA damage in lymphocytes of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. BioFactors. 2007;31(3-4):191-200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/biof.5520310306

- Youn MJ, Kim JK, Park SY, et al. Chaga mushroom (Inonotus obliquus ) induces G0/G1 arrest and apoptosis in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;14(4):511. doi:https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.14.511

- Glamočlija J, Ćirić A, Nikolić M, et al. Chemical characterization and biological activity of Chaga (Inonotus obliquus), a medicinal “mushroom.” Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2015;162:323-332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2014.12.069

- Bach F, Zielinski AAF, Helm CV, et al. Bio compounds of edible mushrooms: in vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activities. LWT. 2019;107:214-220. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2019.03.0177

- Kwon O, Kim Y, Paek JH, et al. Chaga mushroom-induced oxalate nephropathy that clinically manifested as nephrotic syndrome. Medicine. 2022;101(10):e28997. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000028997

- Plehn S, Wagle S, Rupasinghe HPV. Chaga mushroom triterpenoids as adjuncts to minimally invasive cancer therapies: A review. Current Research in Toxicology. 2023;5:100137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crtox.2023.100137

- Dosychev EA, Bystrova VN. [Treatment o psoriasis using “Chaga” fungus preparations]. Vestnik Dermatologii I Venerologii. 1973;47(5):79-83. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4755970/

- Powell M. Medicinal Mushrooms : A Clinical Guide. Mycology Press, An Imprint Of Bamboo Publishing Ltd; 2014.

- https://www.herbalreality.com/herbalism/western-herbal-medicine/chaga-mushroom-medicinal-properties/

- Hunter M. The Sustainability Debate on Chaga. blueridgechagaconnection.com. Published March 1, 2020. Accessed March 12, 2024. https://blueridgechagaconnection.com/2020/03/01/the-sustainability-debate-on-chaga/

- Miina J, Peltola R, Veteli P, et al. Inoculation success of Inonotus obliquus in living birch (Betula spp.). Forest Ecology and Management. 2021;492:119244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2021.119244