-

How does it feel?

Black Cohosh has a pungent, mildly bitter cooling effect. With an earthy, slightly mushroomy flavour (as is commonly found with roots). A fairly ground feeling is noticed after using this medicine which could be described as a sense of harmony in the nervous system.

-

What can I use it for?

Reproductive conditions

Reproductive conditionsBlack Cohosh has a wealth of medicinal applications in the treatment of conditions of the female reproductive system and for neuro-muscular conditions.

It would be a great herb to consider using to help with painful menstruation, premenstrual syndrome or menopausal symptoms, depending on the nature of the condition (2, 7, 8). For example, premenstrual syndrome can be the result of specific hormonal imbalances, for some of which there may be a better alternative. This is something that a trained Medical Herbalist would be able to help you identify. Clinical herbalists can be found here and seeing one is the best option for chronic and complex conditions.

Neurological conditions

Some of the most popular applications of Black Cohosh are in the treatment of headaches, tinnitus and vertigo. As a herb that balances constriction in the micro-capillaries, whilst acting to reduce nerve tension, it can be an effective option to support those who are prone to the above conditions (2, 7, 8).

As a relaxant it can be used to treat a number of different types of headaches such as migraine, cluster and ophthalmic headaches (used with caution in cases of true migraines as can occasionally induce vomiting) (8). Anyone suffering from chronic headaches should seek professional medical advice, to identify the cause and rule out any more serious health conditions.

Rheumatic conditions

Perhaps one of its most renowned actions is as a powerful antispasmodic. This can be useful for the treatment of both nervous or muscular problems such as rheumatic conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis and muscular problems as it acts both as a powerful anti-inflammatory and antispasmodic.

Respiratory conditions

Black Cohosh has some value in treatment of conditions that present with respiratory tension or spasmodic tissue state in the lungs. This would include that found in asthma and pertussis (whooping cough). It is herb that also supports the natural processes of a viral fever, such as to slow the heart rate whilst supporting a healthy sweat, which improves viral detoxification (7, 8, 9, 12).

-

Into the heart of black cohosh

A pungent cooling medicine, with an acridity known to soften and relieve tensions throughout the cardiovasular system and the nervous system. Black Cohosh can be applied for all of the physiological conditions mentioned above, however it would be an excellent choice where anxiety and panic attacks may be additional factors (7, 8). As a mildly bitter pungent herb, black cohosh will deliver a grounding effect. As it is able to offer a relaxant action upon the cardiovascular and nervous system, this plant brings a sense of earthing, whilst it directly neutralises overactivity in the ANS (autonomic nervous system).

A pungent cooling medicine, with an acridity known to soften and relieve tensions throughout the cardiovasular system and the nervous system. Black Cohosh can be applied for all of the physiological conditions mentioned above, however it would be an excellent choice where anxiety and panic attacks may be additional factors (7, 8). As a mildly bitter pungent herb, black cohosh will deliver a grounding effect. As it is able to offer a relaxant action upon the cardiovascular and nervous system, this plant brings a sense of earthing, whilst it directly neutralises overactivity in the ANS (autonomic nervous system). Black Cohosh works to reduce over activity in both the parasympathetic and the sympathetic nervous system. These are the two branches of the ANS which innovate all of our visceral organs and automatic processes. Overactivity in these systems can cause digestive and sleep issues or high blood pressure and a fast heart rate, among other symptoms respectively (7, 8). Black Cohosh would therefore be an excellent herb of choice to support the balance of the ANS, particularly where this imbalance is caused by prolonged exposure to stress hormones (6, 7).

-

Traditional uses

Black Cohosh has been used in Native American medicine for a wide range of gynaecological conditions and rheumatic complaints. Traditionally used as a diaphoretic in agues and fevers of viral illness. Reportedly, it cured many cases of yellow fever and smallpox. It was also believed in Native American medicine to be an antidote to rattlesnake venom, used as a root poultice (10,12).

Black Cohosh has been used in Native American medicine for a wide range of gynaecological conditions and rheumatic complaints. Traditionally used as a diaphoretic in agues and fevers of viral illness. Reportedly, it cured many cases of yellow fever and smallpox. It was also believed in Native American medicine to be an antidote to rattlesnake venom, used as a root poultice (10,12). The Eclectics prescribed Black Cohosh in the form of fluid extract for prophylactic treatment of smallpox, also for inflammatory rheumatism and the neuralgias (13).

It has long been used in Traditional Western Herbal Medicine as a herb to bring on a delayed menstruation, supporting the symptoms of menopause in the post- reproductive years. It is a vascular antispasmodic, that is also traditionally used in high blood pressure (10).

It has a long-standing history of use for persistent coughing, particularly that of whooping cough. Black cohosh acts as an expectorant (promoting coughing/ clearing of the lungs), whilst reducing rapidity of the pulse and increasing perspiration. In essence, it supports the process of a natural fever and is a traditional approach used by herbal physicians to increase recovery outcomes (12).

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Chinese energetics

-

What practitioners say

This herb has long been regarded as an important medicine on the shelves of a herbalists dispensary, with a number of well documented applications for treatment of conditions in the neuromuscular system and the female reproductive system. The actions of this plant would likely be worked into a prescription for their powerfully physiological properties, as a main player so to speak. This herb is used for producing effective symptomatic relief of the earlier mentioned conditions of the reproductive system, such as painful menstruation and menopausal symptoms.

This herb has long been regarded as an important medicine on the shelves of a herbalists dispensary, with a number of well documented applications for treatment of conditions in the neuromuscular system and the female reproductive system. The actions of this plant would likely be worked into a prescription for their powerfully physiological properties, as a main player so to speak. This herb is used for producing effective symptomatic relief of the earlier mentioned conditions of the reproductive system, such as painful menstruation and menopausal symptoms.It is also an excellent choice where menopausal symptoms also present alongside osteoporosis or rheumatic arthritis. It is a herb that combines well with valerian for the treatment of neuralgic conditions such as lumbago, myalgia, chorea, sciatica, intercostal and trigeminal neuralgia (2, 7).

Many herbalists use this plant in the treatment of inner ear conditions such as tinnitus, vertigo and Menieres disease. This would be most useful where the cause is due to vaso-constriction, high blood pressure or of neuromuscular problems (7, 8).

-

Research

Much of the research into the effects of Black Cohosh have been focused on the treatment of menopausal symptoms and whether or not it works via an oestrogenic pathways or indirectly via the CNS (central nervous system).

Much of the research into the effects of Black Cohosh have been focused on the treatment of menopausal symptoms and whether or not it works via an oestrogenic pathways or indirectly via the CNS (central nervous system). However, the importance of this plant in treatment of other conditions such as those in the nervous system should not be overlooked. This is certainly a plant with a great value for many other health problems which requires more research.

Menopause

In a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial 84 early or post-menopausal participants with a moderate to high Greene Climacteric Scale (GCS) score (a scale used to measure of menopausal symptoms) were randomly allocated into treatment using either 6.5 mg of dried extract of Black cohosh roots daily or a control (placebo). The participants took one tablet per day for 8 weeks (4).

The GCS total score in the treatment group was significantly lower than that in the control group at both week 4 and week 8. The results clearly displayed a significant improvement of menopausal symptoms than that of the control group in all GCS subscale scores (vasomotor, psychiatric, physical, and sexual symptoms (4).

In another double-blind, CE- and placebo-controlled study an extract of black cohosh demonstrated a clear reduction in oestrogen deficiency symptoms to the same degree as conjugated oestrogens. Improvements were measured on all climacteric complaints, somatic complaints, mental and emotional state, sweating episodes with a significant improvement in sleep quality among the test group (10).

The literature to date does not fully confirm a direct oestrogenic mechanism to explain the effects of black cohosh, though it is not ruled out entirely. It is however thought that black cohosh may instead act on the neural pathways via its effects on neurotransmitters in the CNS (central nervous system) that modulate the thermoregulation system (6).

Black Cohosh has been the subject of a huge amount of scientific research, both through clinical trials and studies on its active compounds. In both, there seems to be conflicting outcomes in terms of the directly oestrogenic effects of Black Cohosh.

This is often the way with the scientific research carried out to assess the effectiveness of a chemically complex herbal medicine, whose efficacy is difficult to measure within the reductionist nature of modern research.

It is generally agreed however among the herbal community that black cohosh is a hormonal amphoteric (herb that can balance, according to the body’s needs). This is an action often seen in medicinal plants due to the dynamic and synergistic actions of their chemistry (6,7).

Research has been unable to conclude whether Black Cohosh exerts these effects by acting as an oestrogen in the brain. It is most likely however that it may alleviate hot flashes by acting on neurotransmitter systems (specifically serotonergic neurons) in the thermoregulatory hypothalamus via selective serotonin reuptake. It is also considered that compounds in Black Cohosh, by this same mechanism may indirectly interact with the oestrogenic systems (6, 7, 8).

-

Did you know?

The origin of its folk name ‘black snakeroot’ or ‘rattlesnake root’, refers to its traditional use in North America to treat snakebites, including that of the rattlesnake). Also known as bugbane, the Latin word ‘Cimicifuga’ means ‘to chase insects away’ due to another early use of this plant as an insect repellant.

Additional information

-

Botanical description

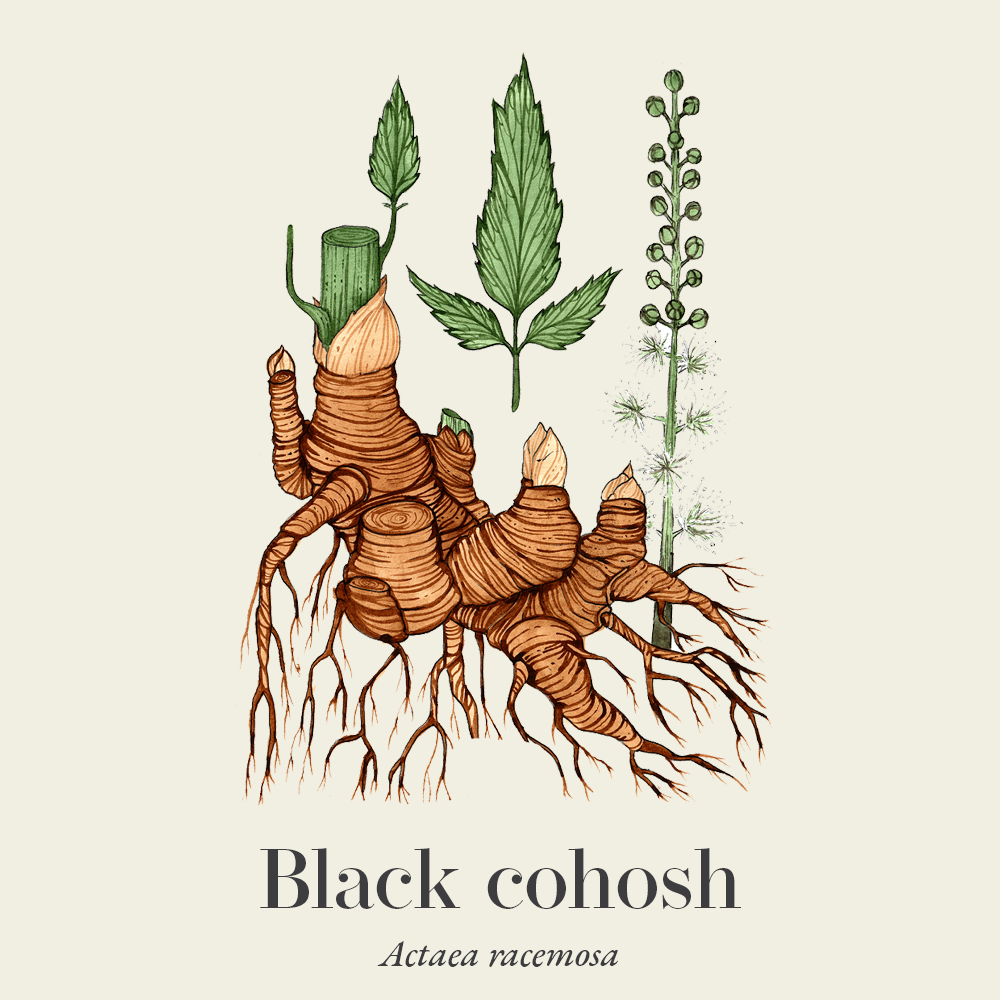

Native to the deciduous woodlands of North America, Black Cohosh is a herbaceous perennial, reaching a height of approximately 2m or more. Flowering between June and September, this plant produces tall, flower stems that branch into several long narrows racemes (flower spikes) with small, creamy-white flowers. These flower spikes have a tendency to lean slightly towards the sun.

Leaves are compound (made up of a number of smaller leaflets) and usually mid to dark green and serrated, with 2-5 sets branching out in groups of three along the petiole (leaf stem).

Black cohosh grows primarily on the moist, fertile slopes of deciduous woodlands along the eastern United States and south Eastern Canada. A beautiful plant much loved as a garden ornamental in temperate regions.

As the global demand increases for the medicinal uses of this plant, black cohosh has been under some concern by conservationists and regulators as it is almost exclusively harvested from the wild.

-

Common names

- Black cohosh

- Black snakeroot

- Cohosh bugbane

- Cohosh bugbane

-

Safety

Black cohosh is safe when taken appropriately for up to one year, however it is a herb that has occasionally reported to have caused minor side effects (low incidence) and with some drug interactions to consider (see below).

Black Cohosh is NOT to be taken during pregnancy or lactation.

-

Interactions

Cisplatin: A medication the is used in cancer treatments. Black Cohosh may decrease the effectiveness of this drug.

Medications metabolised in the liver: (Cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) substrates). Black Cohosh might change how quickly these medications are broken down by the liver, possibly changing their effects or causing side effects.

Medications that can harm the liver: such as Atorvastatin (Lipitor) and other hepatotoxic drugs interacts with Black Cohosh.

Medications moved by pumps in cells (Organic anion-transporting polypeptide substrates): Some medications are moved in and out of cells by pumps. Black cohosh might change how these pumps work and change how much medication stays in the body. In some cases, this might change the effects and side effects of a medication.

-

Contraindications

Side effects: Although rare, Black Cohosh has been noted to cause mild side effects in a small number of people such as gastric upset, headache, rash and a feeling of heaviness. Should these effects be experienced, consult a professional medical herbalist to assist with appropriate guidance.

Liver disease: In a systematic review of published clinical trials, in a majority there is a clear indication of efficacy for use of extracts of black cohosh (Actaea racemosa L.) to improve menopause-related symptoms. However, there are some reports of hepatotoxicity.

These case reports were confounded on the basis of inadequate details/ evidence of pre-existing underlying liver disease, autoimmune diseases or those taking medications that may have impacted liver function. It would still however be advised to seek guidance from a professional medical herbalist before taking Black Cohosh if you have a liver condition (5, 6).

Breast cancer: Black cohosh may worsen existing breast cancer. People who have breast cancer or who have had breast cancer in the past, and those at high-risk for breast cancer, should avoid black cohosh or consult a medical herbalist for appropriate guidance.

Hormone-sensitive conditions: such as endometriosis, fibroids, ovarian cancer, uterine cancer. Black cohosh contains oestrogen like compounds therefore it may worsen conditions that are sensitive to oestrogen. Avoid black cohosh if you have a condition that could be affected by female hormones or consult a medical herbalist for appropriate guidance.

-

Preparations

- Tincture

- Dried root

- Decoction

- Capsule

- Fluid extract

-

Dosage

Tincture: (1:5 in 60%) dosage is 2- 4ml three times.

Decoction: (1 cup of water/ 1 tsp dried root- simmered 10- 15 minutes and strained) to be drunk x 3 cups a day (alternatively make 3 cups worth and reheat throughout the day).

-

Plant parts used

Root and rhizome (often dried root is preferred, this is because compounds in fresh root are more powerfully sedative, these compounds are less potent after drying).

-

Constituents

- Tetrscyclic triterpene glycosides (steroidal saponins) – acetic and cimigoside (effects on the hypothalamic – pituitary receptor sites.

- Isoflavone – formonocetin – binds to oestrogen receptor sites.

- Resin (unto 20%) – cimicifugin – oestrogenic.

- Ferrulic acid – anti-inflammatory.

- Tannins. Volatile oils. Fatty acids. Salicylic acid. 27 deoxyacetin – oestrogen like activity.

- Black Cohosh is thought to produce both anti-oestrogenic and anti LH (luteinising hormone) enhancing oestrogen activity (7).

-

References

- D. Hoffmann, (2003). Medical Herbalism: The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Healing Arts Press. India. Replica Press Put. Ltd.

- British Herbal Medicine Association. Scientific Committee (2003). A guide to traditional herbal medicines : a sourcebook of accepted traditional uses of medicinal plants within Europe. London: British Herbal Medicine Association.

- Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology and National Cancer Institute (NCI) (2016). A Phase III Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Crossover Trial Of Black Cohosh In The Management Of Hot Flashes. [online] clinicaltrials.gov. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00060320 [Accessed 13 May 2022].

- Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S., Shahnazi, M., Nahaee, J. and Bayatipayan, S. (2013). Efficacy of black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa L.) in treating early symptoms of menopause: a randomized clinical trial. Chinese Medicine, [online] 8(1), p.20. doi:10.1186/1749-8546-8-20.

- Mahady, G.B., Doyle, B., Locklear, T., Cotler, S.J., Guzman-Hartman, G. and Krishnaraj, R. (2006). Black Cohosh (Actaea Racemosa) for the Mitigation of Menopausal Symptoms: Recent Developments in Clinical Safety and Efficacy. Women’s Health, 2(5), pp.783–793. doi:10.2217/17455057.2.5.783.

- Ruhlen, R.L., Sun, G.Y. and Sauter, E.R. (2008). Black Cohosh: Insights into its Mechanism(s) of Action. Integrative Medicine Insights, [online] 3, pp.21–32. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3046019/.

- Menzies-Trull, C. (2013). Herbal medicine keys to physiomedicalism including pharmacopoeia. Newcastle: Faculty Of Physiomedical Herbal Medicine (Fphm).

- Kenner, D. and Yves Requena (2001). Botanical medicine : a European professional perspective. Brookline, Mass.: Paradigm Publications.

- Burdette JE, Liu J, Chen SN, et al. Black cohosh acts as a mixed competitive ligand and partial agonist of the serotonin receptor. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51:5661–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Ref list]

- Wuttke, W., Rauš, K. and Gorkow, C. (2006). Efficacy and tolerability of the Black cohosh (Actaea racemosa) ethanolic extract BNO 1055 on climacteric complaints: A double-blind, placebo- and conjugated estrogens-controlled study. Maturitas, 55, pp.S83–S91. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2006.06.020.

- Trickey, R. and Trickey Enterprises (2011). Women, hormones & the menstrual cycle. Fairfield, Vic.: Melbourne Holistic Health Group.

- Grieve, M. (1998). A modern herbal : the medicinal, culinary, cosmetic and economic properties, cultivation and folklore of herbs, grasses, fungi, shrubs and trees with all their modern scientific uses. London England: Tiger Books International.

- www.henriettes-herb.com. (n.d.). Black Cohosh. | Henriette’s Herbal Homepage. [online] Available at: https://www.henriettes-herb.com/articles/cohosh.html [Accessed 16 May 2022].

Reproductive conditions

Reproductive conditions A pungent cooling medicine, with an acridity known to soften and relieve tensions throughout the cardiovasular system and the nervous system. Black Cohosh can be applied for all of the physiological conditions mentioned above, however it would be an excellent choice where anxiety and panic attacks may be additional factors (7, 8). As a mildly bitter pungent herb, black cohosh will deliver a grounding effect. As it is able to offer a relaxant action upon the cardiovascular and nervous system, this plant brings a sense of earthing, whilst it directly neutralises overactivity in the ANS (autonomic nervous system).

A pungent cooling medicine, with an acridity known to soften and relieve tensions throughout the cardiovasular system and the nervous system. Black Cohosh can be applied for all of the physiological conditions mentioned above, however it would be an excellent choice where anxiety and panic attacks may be additional factors (7, 8). As a mildly bitter pungent herb, black cohosh will deliver a grounding effect. As it is able to offer a relaxant action upon the cardiovascular and nervous system, this plant brings a sense of earthing, whilst it directly neutralises overactivity in the ANS (autonomic nervous system).  Black Cohosh has been used in Native American medicine for a wide range of gynaecological conditions and rheumatic complaints. Traditionally used as a diaphoretic in agues and fevers of viral illness. Reportedly, it cured many cases of yellow fever and smallpox. It was also believed in Native American medicine to be an antidote to rattlesnake venom, used as a root poultice (10,12).

Black Cohosh has been used in Native American medicine for a wide range of gynaecological conditions and rheumatic complaints. Traditionally used as a diaphoretic in agues and fevers of viral illness. Reportedly, it cured many cases of yellow fever and smallpox. It was also believed in Native American medicine to be an antidote to rattlesnake venom, used as a root poultice (10,12).  This herb has long been regarded as an important medicine on the shelves of a herbalists dispensary, with a number of well documented applications for treatment of conditions in the neuromuscular system and the female reproductive system. The actions of this plant would likely be worked into a prescription for their powerfully physiological properties, as a main player so to speak. This herb is used for producing effective symptomatic relief of the earlier mentioned conditions of the reproductive system, such as painful menstruation and menopausal symptoms.

This herb has long been regarded as an important medicine on the shelves of a herbalists dispensary, with a number of well documented applications for treatment of conditions in the neuromuscular system and the female reproductive system. The actions of this plant would likely be worked into a prescription for their powerfully physiological properties, as a main player so to speak. This herb is used for producing effective symptomatic relief of the earlier mentioned conditions of the reproductive system, such as painful menstruation and menopausal symptoms. Much of the research into the effects of Black Cohosh have been focused on the treatment of menopausal symptoms and whether or not it works via an oestrogenic pathways or indirectly via the CNS (central nervous system).

Much of the research into the effects of Black Cohosh have been focused on the treatment of menopausal symptoms and whether or not it works via an oestrogenic pathways or indirectly via the CNS (central nervous system).