-

How does it feel?

The overwhelming taste of ginkgo leaf is bitterness. It is immediate, direct and persists for a long time in the mouth. However, without a history of use it is difficult to link this to any traditional therapeutic quality.

-

What can I use it for?

Concentrated ginkgo extracts can be used to improve blood flow, tissue oxygenation and nutrition, and to protect nervous tissue. They enhance memory and cognitive function, especially in the elderly and have also been used in some cases of tinnitus, dizziness and headaches. Some symptoms of atherosclerosis such as intermittent claudication (pain in the lower legs on walking even short distances) may also be relieved. Ginkgo extract has been taken as a supplement to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, to improve retinal blood flow and as a remedy to manage glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration.

Concentrated ginkgo extracts can be used to improve blood flow, tissue oxygenation and nutrition, and to protect nervous tissue. They enhance memory and cognitive function, especially in the elderly and have also been used in some cases of tinnitus, dizziness and headaches. Some symptoms of atherosclerosis such as intermittent claudication (pain in the lower legs on walking even short distances) may also be relieved. Ginkgo extract has been taken as a supplement to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, to improve retinal blood flow and as a remedy to manage glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration.The extract has also been shown to reduce the impact of a range of stressors and to reduce anxiety and depression.

However, given what is known about:

- The widespread adulteration of commercial ginkgo extracts

- The threat of allergenic constituents in these extracts

- The lack of evidence for ginkgo leaf itself

One should choose either an EGb761 extract or one with similar constituents and quality assurances.

The use of other preparations of ginkgo has become widespread among herbal practitioners and it will be important to generate a new evidence base to support its continuing use. This will become an interesting future project.

-

Into the heart of ginkgo

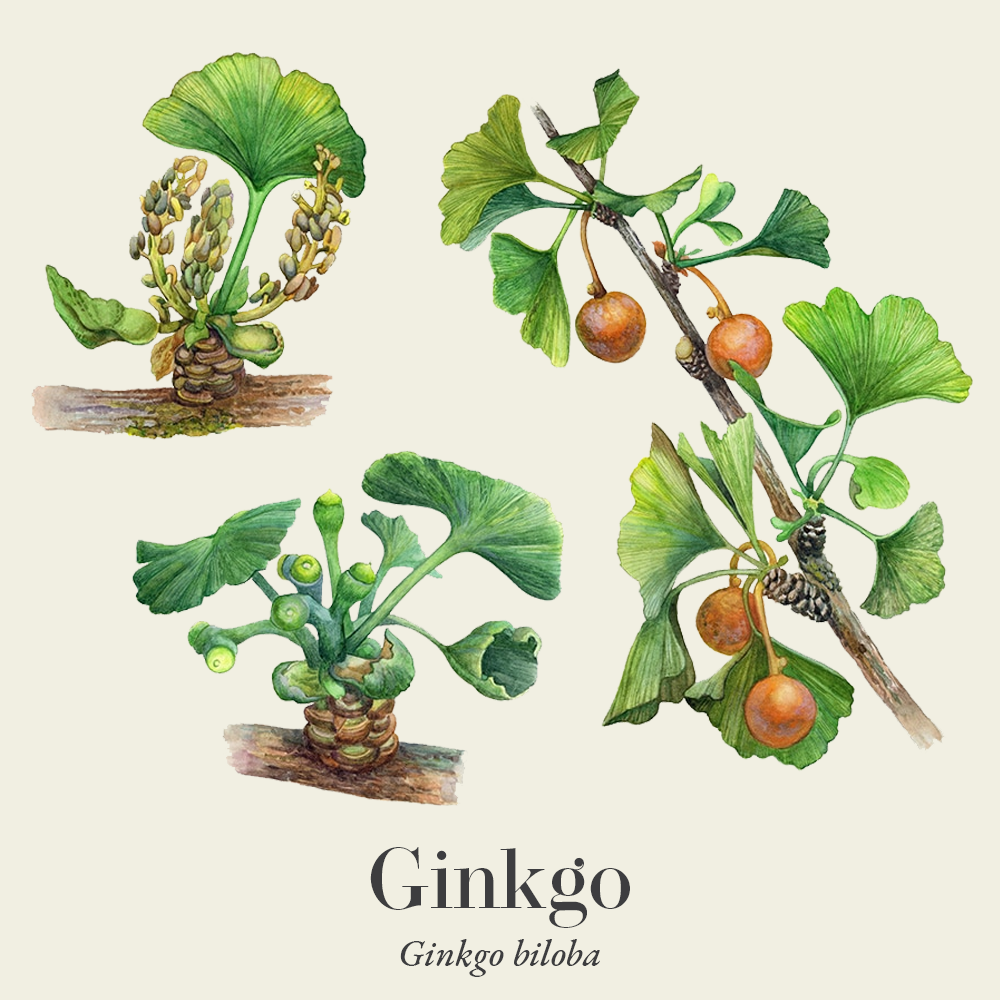

Ginkgo leaves and fruit (Ginkgo biloba) While ginkgo nuts are used in traditional Chinese medicine (for lung and kidney ailments), the modern use of the green leaf is entirely due to scientific discovery. In the 1960s a group of German scientists set out to investigate the effects of novel herbs on circulation. In traditional German healthcare circulatory disturbances have been default explanations for a wide range of illnesses, including ageing and cognitive decline. Perhaps attracted by the heart-shaped leaves (Herz is the key circulatory metaphor in German culture) they investigated further and developed a concentrated ginkgo extract. This was standardised for flavonoid content and patented soon after.

The original therapeutic focus was improving peripheral circulation to the brain. This fits in with another concept popular in Germany of ‘cerebral insufficiency’ with symptoms including difficulties in concentration and memory, absentmindedness, confusion, lack of energy, tiredness, decreased physical performance, depressive mood, anxiety, dizziness, tinnitus and headaches. These symptoms have also been associated with the early stages of dementia. The assumption is that anything that improves circulation to the brain would help in these conditions. Ginkgo was also prescribed for tinnitus, and in reducing clotting in cardiovascular diseases. Cerebral insufficiency is not much recognised outside continental Europe and the use of ginkgo as a prescription medicine is largely confined to these countries. The idea is however consistent with herbal therapeutics and the ginkgo story opens the door to other similar approaches.

Wider acceptance of ginkgo has followed recognition of its potential neuroprotective effects and EGb761 is emerging as an important phytomedicine treatment for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. To support the latter benefit there is laboratory evidence for a reduction in platelet-activating factor (PAF), especially by the terpenes (ginkgolides) which could justify the use of ginkgo extract also in asthma, allergic and immunological reactions. Laboratory evidence also points to a significant effect in protecting mitochondria and other intracellular functions against oxidative stress.

-

Traditional actions

Herbal actions describe therapeutic changes that occur in the body in response to taking a herb. These actions are used to express how a herb physiologically influences cells, tissues, organs or systems. Clinical observations are traditionally what have defined these actions: an increase in urine output, diuretic; improved wound healing, vulnerary; or a reduction in fever, antipyretic. These descriptors too have become a means to group herbs by their effects on the body — herbs with a nervine action have become the nervines, herbs with a bitter action are the bitters. Recognising herbs as members of these groups provides a preliminary familiarity with their mechanisms from which to then develop an understanding of their affinities and nuance and discern their clinical significance.

-

Traditional energetic actions

Herbal energetics are the descriptions Herbalists have given to plants, mushrooms, lichens, foods, and some minerals based on the direct experience of how they taste, feel, and work in the body. All traditional health systems use these principles to explain how the environment we live in and absorb, impacts our health. Find out more about traditional energetic actions in our article “An introduction to herbal energetics“.

Chinese energetics

Western energetics

-

Research

Almost all the clinical research evidence relates to the patented 50:1 extract EGb761 – containing 24% flavone glycosides and 6% terpenoids) at a daily dose typically corresponding to 4 to 16 g of leaf. There is a considerable body of this evidence, with over 400 clinical trials published in the scientific literature.

Much of this work has focused on the potential effects of ginkgo extracts on cognitive decline and dementia, and on various measures of cognitive performance in healthy subjects, such as memory (1,2,3,4).

Other benefits of the extract have been demonstrated, including reduced stress responses (5).

There is very little published evidence for any effects of other ginkgo leaf preparations. One exception is in the case of a 3-5:1 fresh-leaf extract (at 90 mg/day equating to 300-400mg of fresh leaf) in a German-language publication (6).

-

Did you know?

For many years EGb761 was the most frequently used medicine in Germany, routinely prescribed by doctors for their elderly patients, with as usual for medical prescriptions there, the costs largely met by the state. This support was withdrawn in the 1990’s and prescription levels initially fell. However they recovered significantly afterwards, even without reimbursement.

Ironically in most of the English-speaking world ginkgo is classified as a food or dietary supplement.

Additional information

-

Botanical description

Ginkgo biloba is the only member of its family, a gymnosperm that has survived unchanged from the Triassic period. It can grow to a height of over 100m, and some trees have been shown to be over 1000 years. Ginkgo is dioecious (possessing male and female flowers on separate trees) and its leaves have a characteristic fan-like appearance with two lobes (biloba). The seed (or nut) is oily and edible but the seed coat and embryo are bitter.

Because of widespread adulteration of commercial ginkgo extracts with rutin (so as to generate the required high flavonoid levels), a specific quality control method for standardised ginkgo extracts is now a requirement of the United States Pharmacopoeia National Formulary as well as for product registration with the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration.

-

Common names

- Maidenhair tree (Eng)

- Ginkgoblätter (Ger)

- Arbre aux quarante écus (Fr)

- Bai Guo Ye (Mand)

- Baak Gwo Yop (Cant)

-

Safety

There is very little record of problems associated with the use of ginkgo extracts. There is a theoretical risk of a bleeding event or interaction with blood thinning drugs because of its PAF activity but this is neither supported by controlled clinical trials nor by mandatory adverse reporting schemes in Germany and other parts of Europe. Given the very widespread prescription of ginkgo in medical practice there this is a significant assurance of safety.

Because of potential allergic reactions to ginkgolic acids (specified to be less than 5 parts per million in assured extracts), the use of normal tinctures or fluid extracts is not recommended without assurance on this front. Most commercial ginkgo products other than EGb761 have been shown to contain seriously high levels of these allergens (7).

-

Dosage

The daily dose of the 50:1 standardised extract (EGb761) is 120 to 240 mg. This corresponds to 4 to 16 g of leaf, depending on the quality of original leaf.

-

Constituents

The European Pharmacopoeia definitive monograph on dried ginkgo leaf requires a minimum 0.5% flavonoids, calculated as flavone glycosides.

By contrast EGb761 is standardized to 24% ginkgo-flavone glycosides and 6% terpenoids (eg, bilobalide, ginkgolides A, B, C, and J).

Ginkgo leaf also contains ginkgolic acid. This is a strong allergen and in assured extracts levels are specified to be less than 5 parts per million.

Other constituents include procyanidins.

-

References

- Yang G, Wang Y, Sun J, et al. (2016). Ginkgo Biloba for Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.Curr Top Med Chem. 16(5):520-528.

- Kennedy DO, Scholey AB, Wesnes KA. (2000). The dose-dependent cognitive effects of acute administration of Ginkgo biloba to healthy young volunteers.Psychopharmacology (Berl). 151(4):416-423.

- Gieza A, Maier P, Pöppel E. (2003). Effects of Ginkgo biloba on mental functioning in healthy volunteers.Arch Med Res. 34(5):373-381.

- Kaschel R. (2011). Specific memory effects of Ginkgo biloba extract EGb 761 in middle-aged healthy volunteers.Phytomedicine. 18(14):1202-1207.

- Jezova D, Duncko R, Lassanova M, et al. (2002). Reduction of rise in blood pressure and cortisol release during stress by Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb 761) in healthy volunteers.J Physiol Pharmacol. 53(3):337-348.

- Bäurle P, Suter A, WormstallH. (2009) Safety and effectiveness of a traditional ginkgo fresh plant extract – results from a clinical trial. Forsch Komplementmed. 16(3): 156-61.

- Hong Kong Consumer Council. Test Casts Doubt on Clinical Benefits of Ginkgo Leaf Products with Non- Standardized Extract. Choice No. 289, 15 November 2002.

Concentrated ginkgo extracts can be used to improve blood flow, tissue oxygenation and nutrition, and to protect nervous tissue. They enhance memory and cognitive function, especially in the elderly and have also been used in some cases of tinnitus, dizziness and headaches. Some symptoms of atherosclerosis such as intermittent claudication (pain in the lower legs on walking even short distances) may also be relieved. Ginkgo extract has been taken as a supplement to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, to improve retinal blood flow and as a remedy to manage glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration.

Concentrated ginkgo extracts can be used to improve blood flow, tissue oxygenation and nutrition, and to protect nervous tissue. They enhance memory and cognitive function, especially in the elderly and have also been used in some cases of tinnitus, dizziness and headaches. Some symptoms of atherosclerosis such as intermittent claudication (pain in the lower legs on walking even short distances) may also be relieved. Ginkgo extract has been taken as a supplement to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, to improve retinal blood flow and as a remedy to manage glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration.